In 1937, about ten years after talking movies had ended the era of silent film, LIFE magazine—then in its second year of existence—decided to shine a spotlight on the people who were putting the words in the mouths of movie actors.

LIFE staff photographer Paul Dorsey shot portraits of Hollywood’s most important writers. Some of the names of those writers are still recognizable today, while others are more likely to be known only to hardcore cinephiles.

For these writers, LIFE explained, it was the best of times but also the worse of times, because they were well-compensated by movie studios but also largely anonymous. Here’s how the magazine explained their predicament:

The greatest market for literary talent the world has ever known exists today in Hollywood. Writers for movies are better paid than any writers have ever been before. They are less recognized, however, than any equally important writers ever were—except, perhaps, the authors of the King James version of the Bible. These Hollywood Shakespeares have usually been mute, inglorious Miltons.

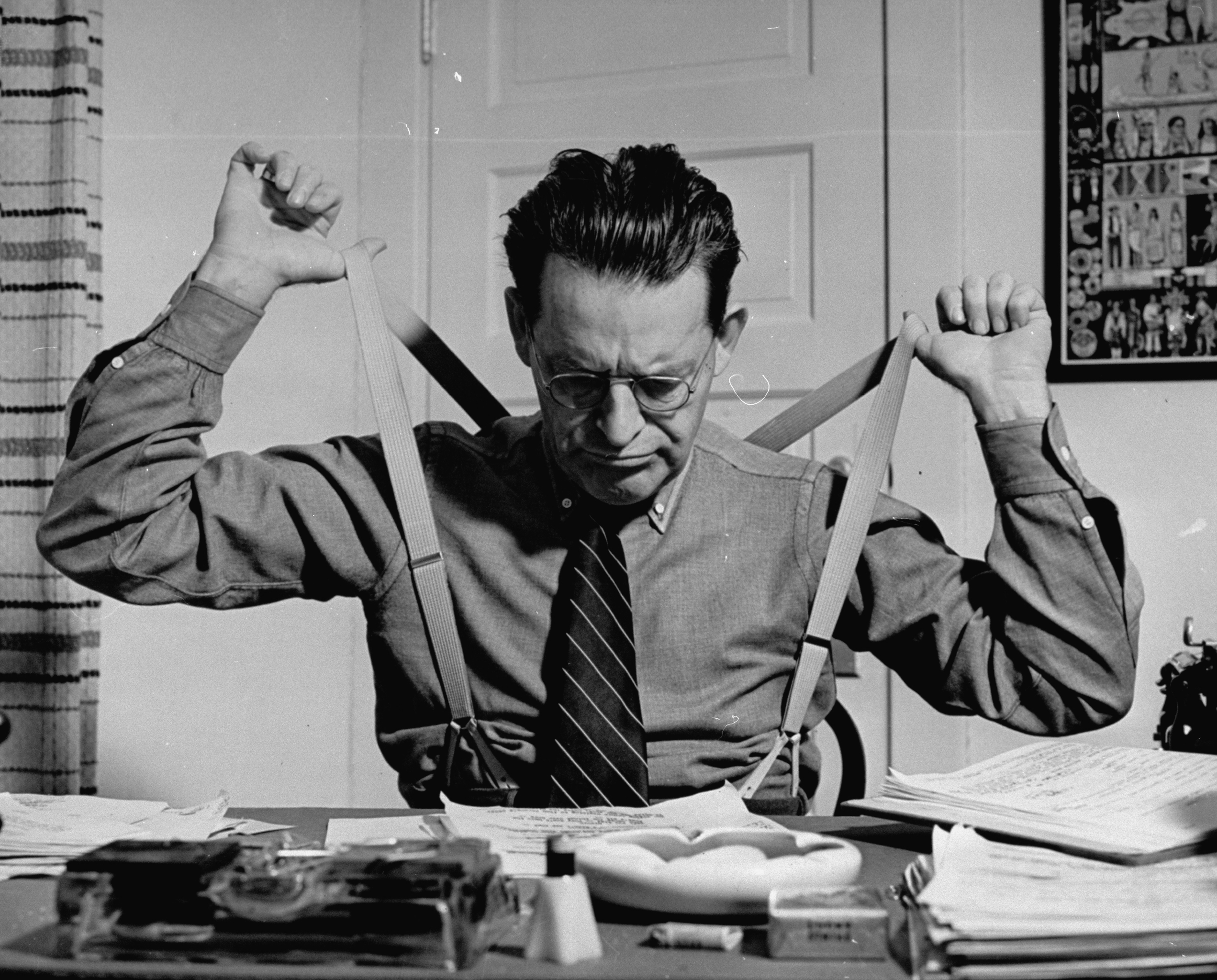

LIFE also believed that some of these writers were frustrated by their secondary role in the filmmaking process, and that this came though when they posed for their portraits—not because the writers looked upset, but rather because of the way some hammed it up for the camera, developing comic concepts for their photos.

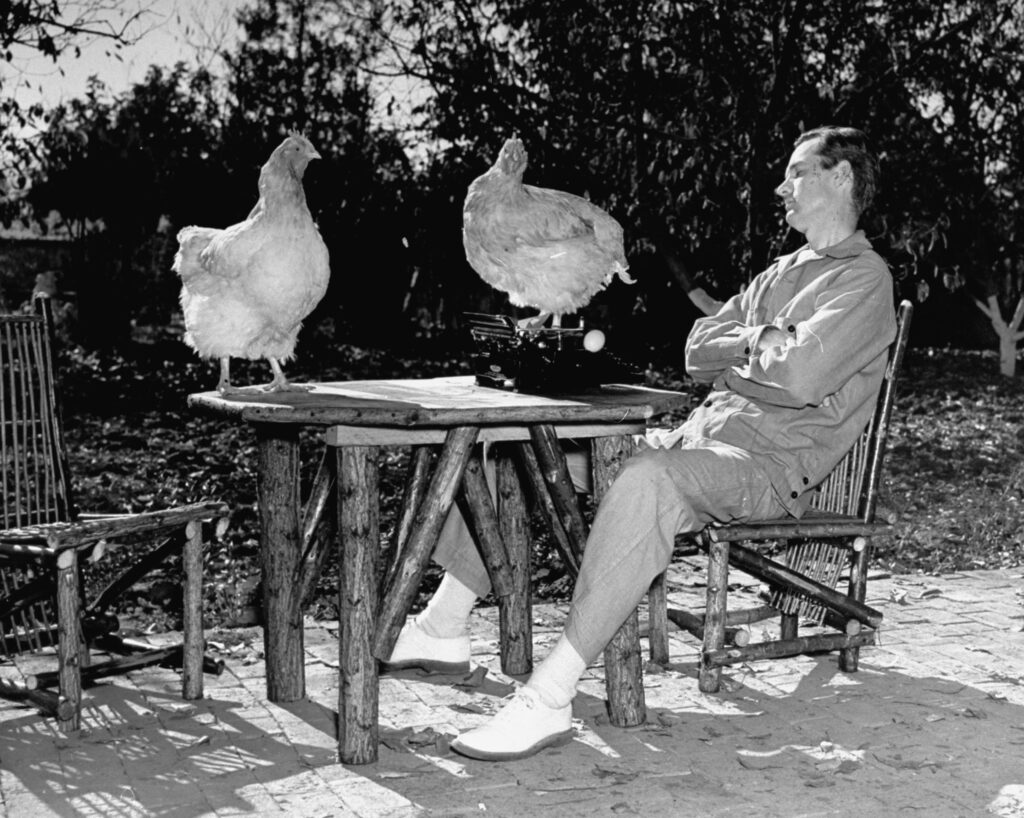

For example, John Lee Mahin, who would be nominated for an Academy Awards for his 1937 film Captain Courageous, posed with chickens on his typewriter to jokingly suggest that his screenplays were about to lay an egg. LIFE theorized, “This urge to act probably represents the revolt of repressed artists who have never had the satisfaction of giving final expression to their inspiration.”

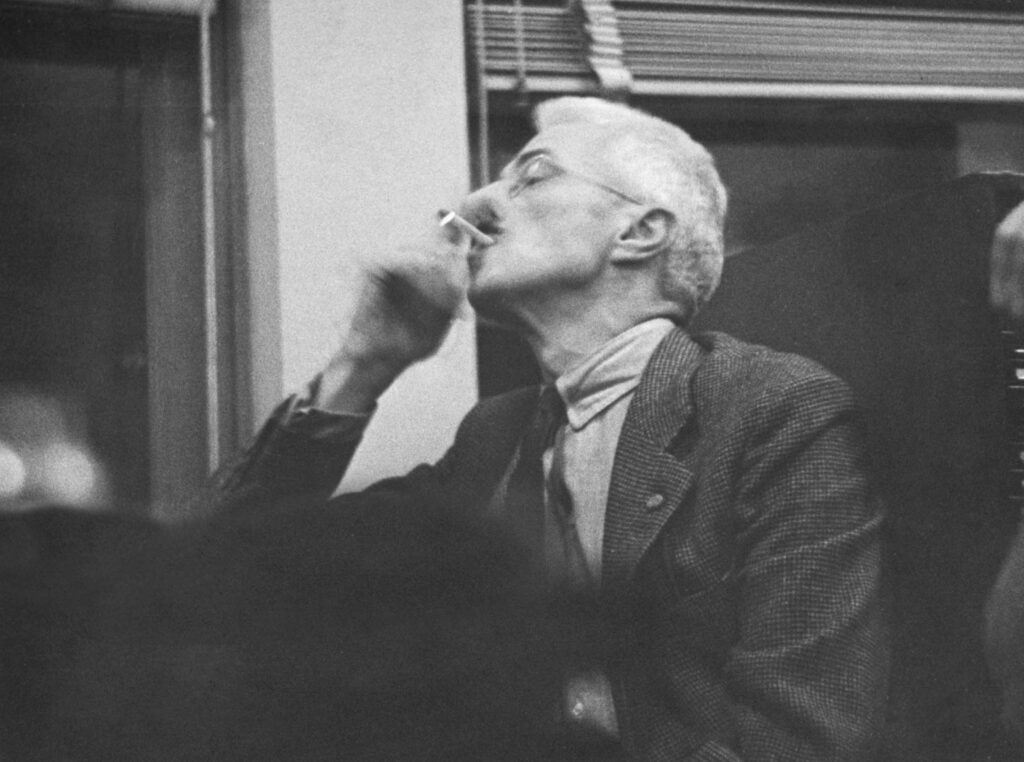

Some of the writers in this portrait collection did have a considerable public profile. Dorothy Parker was glamorous enough that she would eventually become the subject of a movie, and Dashiell Hammett came to Hollywood as a seminal writer of detective fiction. Then there’s Preston Sturges, who would eventually become a director as well as a screenwriter and make classic films such as Sullivan’s Travels and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek. A PBS piece of Sturges said that “The success of these films set the precedent for other writers to become directors.”

Thus did writers gain an avenue to the limelight that did not involve clowning in front of the camera for LIFE.

Writer Dorothy Parker (wearing hat), who co-wrote the original “A Star is Born,” sat with Edwin Justus Mayer, who wrote for many Ernst Lubistch movies, including “To Be or Not To Be,” 1937.

Paul Dorsey/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

MGM screenwriter John Lee Mahin sat at his typewriter with chickens who were supposed to be, along with him, laying an egg, 1937; he would be nominated for an Academy Award for a movie he wrote which came out that year, Captains Courageous..

Paul Dorsey/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Dashiell Hammett, the legendary noir mystery writer, had many of his stories adapted in to movies and wrote original screenplays too.

Paul Dorsey/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Warner Bros. studio writing trio (L-R on sofa) Jerry Wald, Maurice Leo, and Richard Macauley in the throes of writing Gold Diggers in Paris.

Paul Dorsey/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Screenwriter Robert Hopkins received a 1936 Academy Award nomination for the earthquake musical “San Francisco,” starring Clark Gable.

Paul Dorsey/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

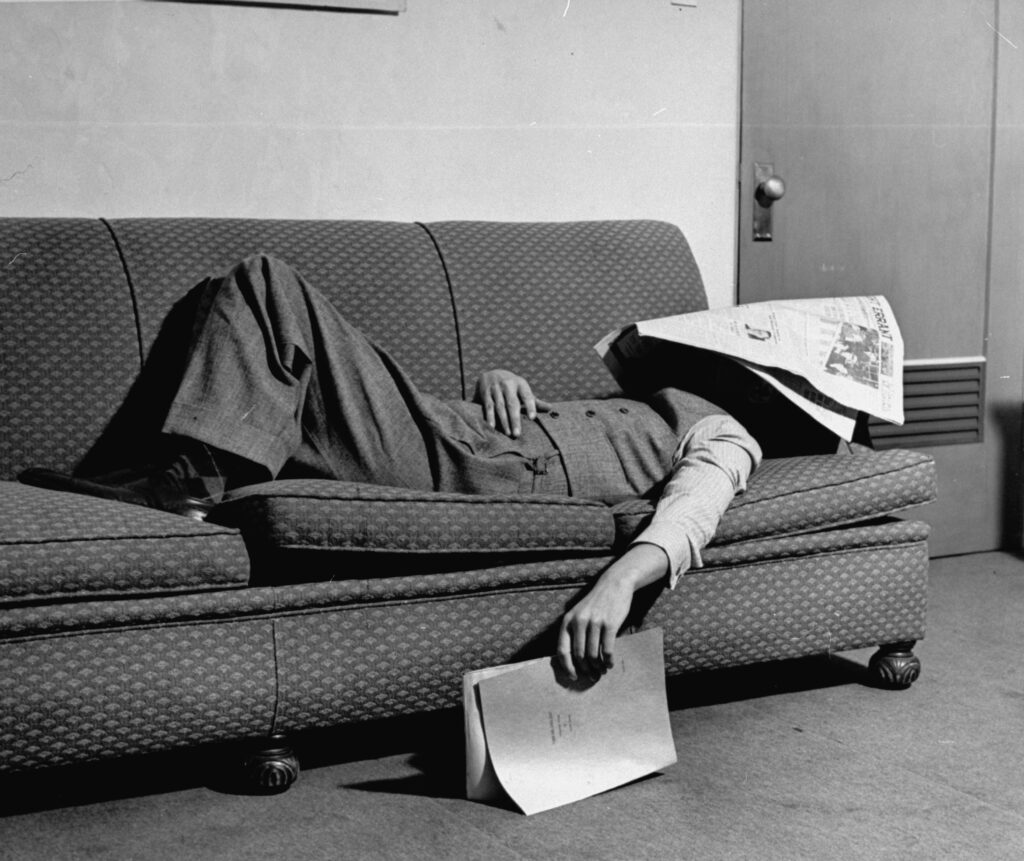

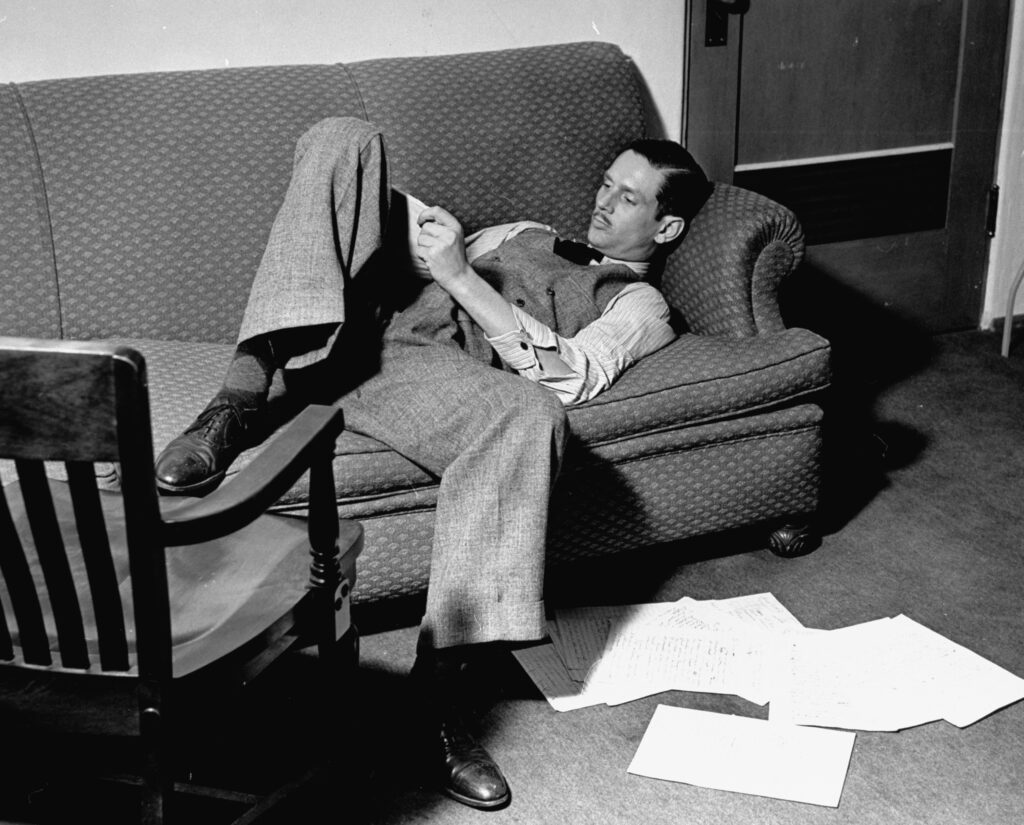

Writer Niven Busch lying on sofa with a newspaper over his face as he took a break from screenwriting, 1937.

Paul Dorsey/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

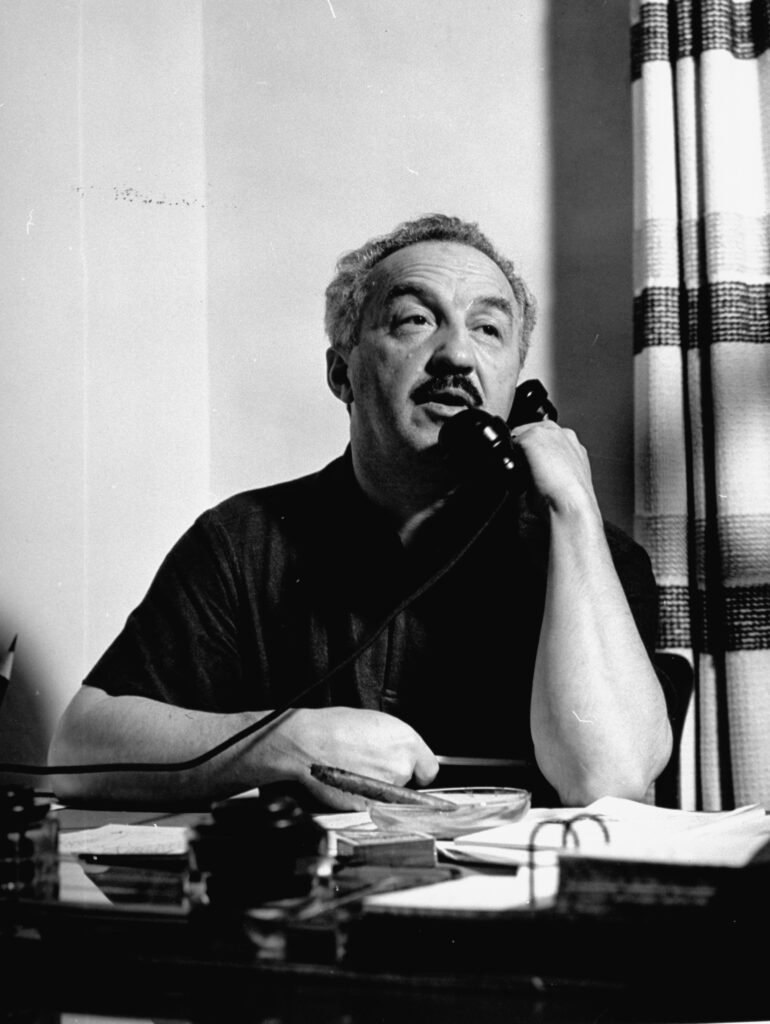

J. P. McEvoy, who wrote screenplays and also many fiction stories that were adapted into movies, is credited with originating the phrase “Cut to the chase.”

Paul Dorsey/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

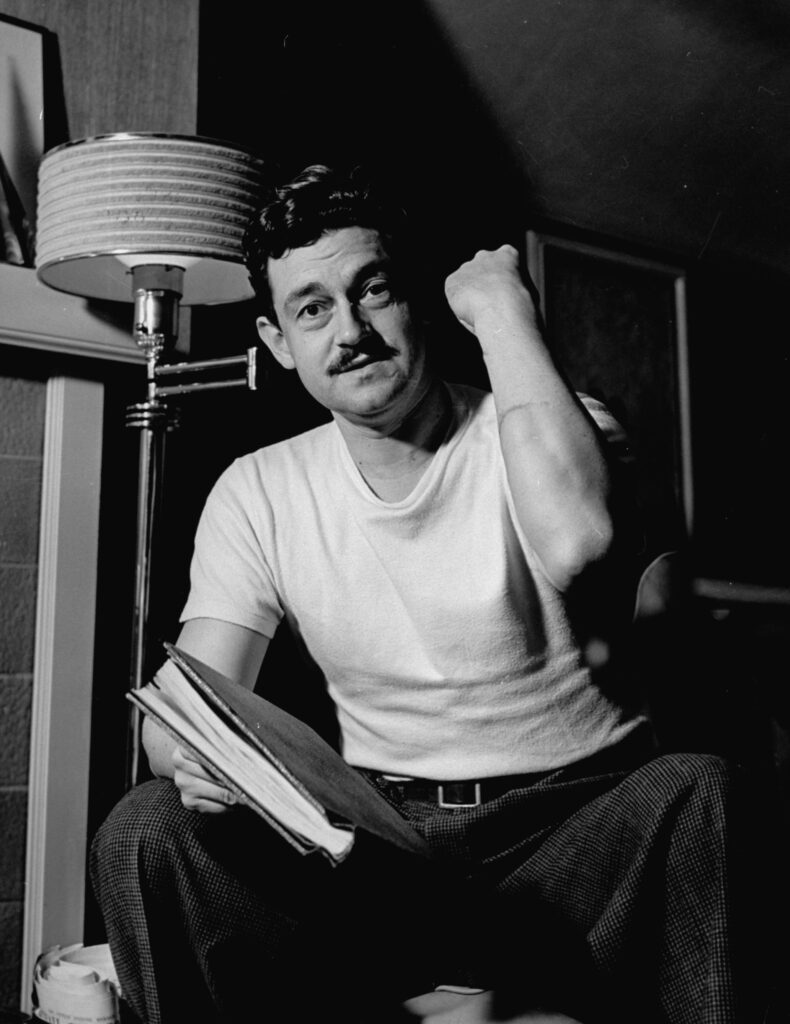

Writer and director Preston Sturges, in white tee shirt, showing cut on arm, in 1937. Sturges would later direct as well as write and become famous for movies such as 1941’s Sullivan’s Travels.

Paul Dorsey/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

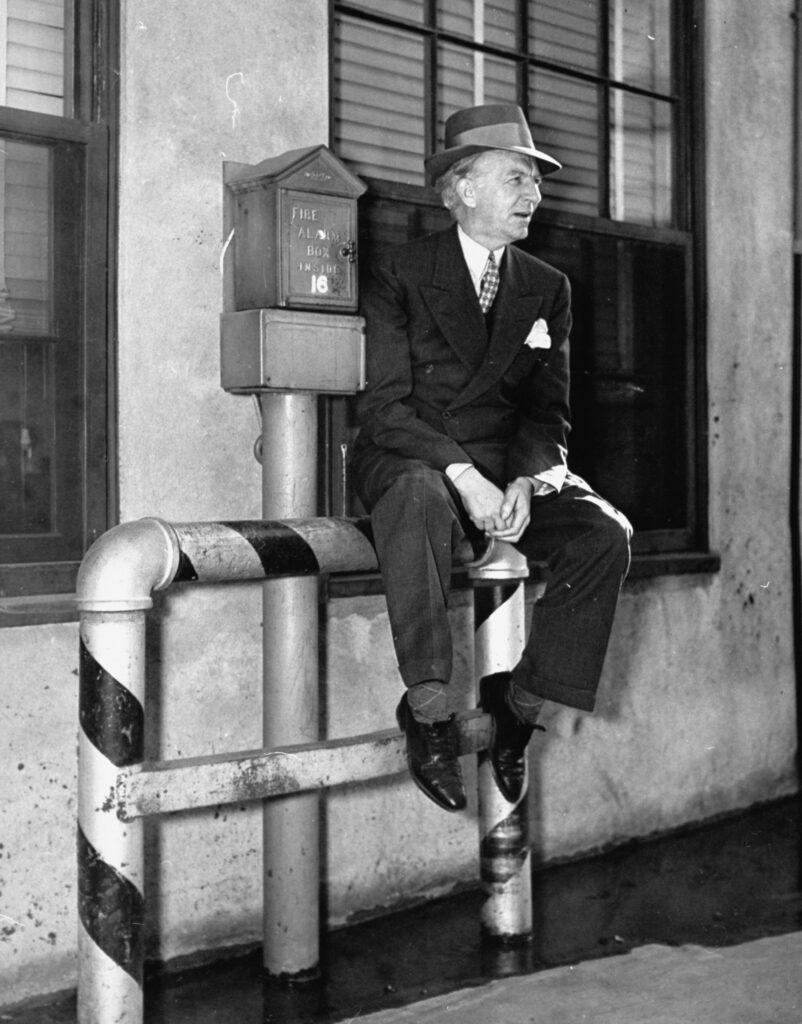

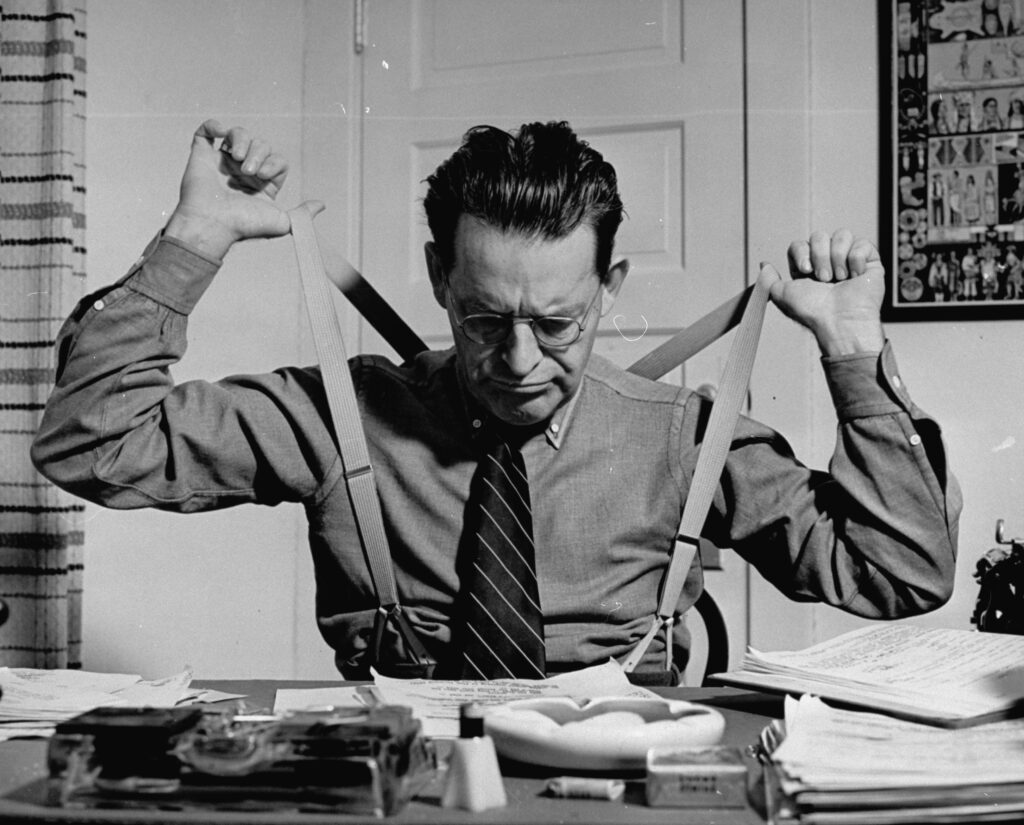

Screenwriter Jack Cunningham was known for being prolific, and he is credited with scripts for more than 130 films.

Paul Dorsey/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Warner Bros. writer Niven Busch worked on screenplay in his office. In 1938 he would be nominated for an Oscar for the musical drama In Old Chicago.

Paul Dorsey/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

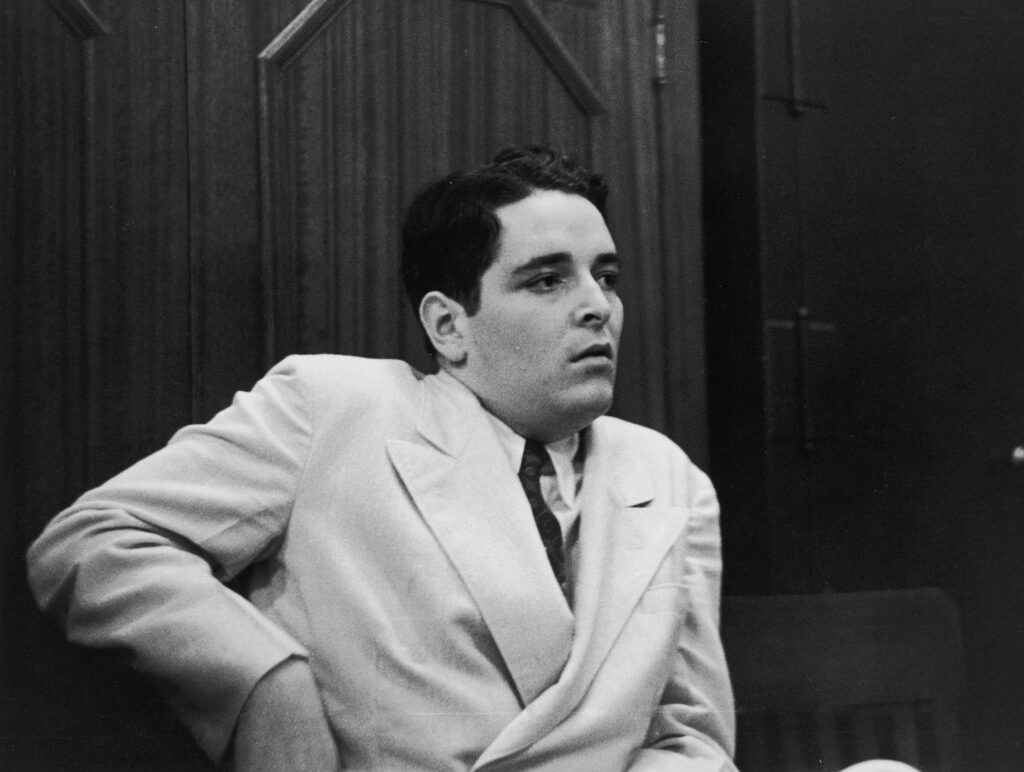

Ring Lardner Jr., early in his screenwriting career in 1937, would win writing Oscars in 1943 for Woman of the year and in 1971 for M*A*S*H.

Paul Dorsey/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock