Jackie Gleason was one of the great entertainers of the early years of television. His most enduring work is the sitcom The Honeymooners, whose original run of 39 episodes from 1955-56 is regarded as a classic of the medium, with Rolling Stone recently rating it as one of Top 10 sitcoms ever. But Gleason had many other TV projects in those years, including hosting the wildly popular variety program The Jackie Gleason Show. He would often introduce acts with the signature phrase, “And away we go.”

LIFE magazine repurposed that catchphrase in its Oct. 5, 1962 issue with the headline “And Away We Go—Again,” for a cover story about Gleason’s return to television as the host of a new variety show.

To promote this show, Gleason chartered a train and went on a cross-country tour. (Why a train? Gleason became afraid of flying after a plane that he was on had to make an emergency landing in Tulsa, Oklahoma after two if its engines failed.) As LIFE reported, “The five-car Gleason special, which cost $90,000 for the ten day trip, carried his company of TV performers and a six-piece jazz band.”

LIFE photographer Allan Grant was along for the ride. Three of Grant’s photos from that train trip ran in the magazine—one of him dancing to the music of the live band on the car, one of him with balloons with the words THE GREAT GLEASON EXPRESS, and another of him celebrating a golf shot with some of his famously exuberant body language during one of the tour’s stops. But Grant shot 844 images in total, and they tell a story that goes beyond the show that Gleason was promoting, creating a deep and broad portrait a comedy star.

First, Jackie Gleason liked to live large, and these photos capture that Rabelaisian aspect of his a public persona. At his tour stops Gleason hits the race track and the pool hall as well as the golf course, and in all these settings he is flanked by the attractive women in his traveling party. On the train, he was photographed dancing with those women while the live band played. It feels like everything is set up so that Gleason could at any moment turn to the camera and utter another one of his catch phrases, “How sweet it is.”

Grant’s camera also captures the less sweet moments. There are shots in which the 46-year-old entertained looks understandably exhausted. Then there are the photo-ops that land flat—such as when Gleason mounts a horse-drawn wagon, or pumps one of those old-time hand rail cars.

Above all, the photos show what it means to have the heart of an entertainer.

Gleason, born in Brooklyn, N.Y., came from difficult circumstances. His older brother died when he was three; his father abandoned the family five years later; his mother died of sepsis when he was 19. Many great comedians forged their audience-pleasing skills during tough times, but wherever it came from, Gleason had a gift for entertaining which showed early, emceeing the school talent showas an eighth grader. He would drop out of high school and take a job as a master of ceremonies at a local theater. He developed not only a quick wit but a vaudevillian versatility with song and dance that would serve him throughout his career.

And long after he had made it big, he continued to work tirelessly. His list of show business credits is improbably long. In addition to his television work he appeared in plenty of movies, earning an Academy Award nomination in 1961 for his portrayal of pool legend Minnesota Fats film in The Hustler. Gleason was also prolific in the field of music, issuing an astounding 47 jazz albums. But, as Gleason told LIFE in 1962, “TV is what I love best,” he said, “and I’m too much of a ham to stay away.”

When Gleason died in 1987 of colon cancer at the age of 71, he had one final joke printed on his mausoluem, adding one final layer of meaning to the phrase “And Away We Go.”

In Grant’s pictures what you see, above all else, is Gleason’s ability to be the life of the party. It’s no mystery why, whenever the train stopped at he met with the public, the halls were packed. When he relocated his show from New York to Miami in 1964, he revved up the Great Gleason Express again for the move down. He certainly a man who enjoyed the ride.

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

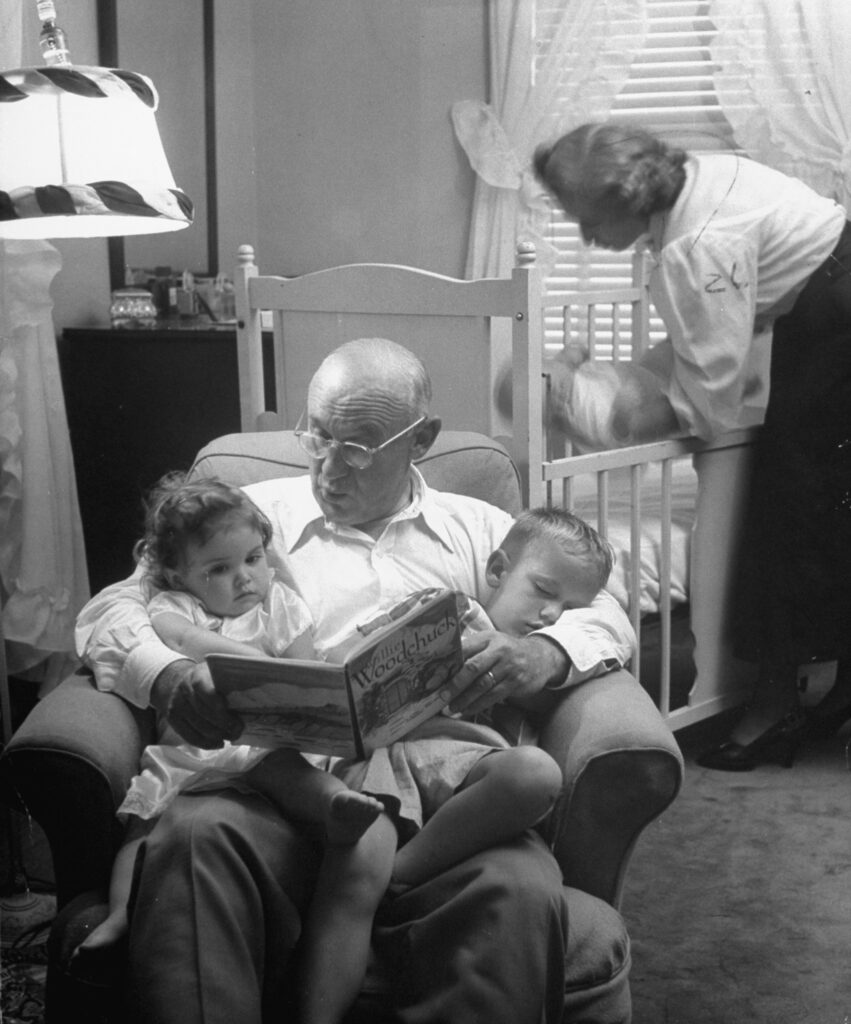

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason celebrated making a shot at the Broadmoore Hotel, Denver, during a 1962 publicity trip promoting his return to TV.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Comedian Jackie Gleason at Broadmoore Hotel, Denver, during publicity trip re his return to TV.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jackie Gleason on “The Great Gleason Express” tour promoting his return to television, 1962.

Allan Grant/Life Pictures/Shutterstock