Times Square has long been known for its advertising displays. The Manhattan crossroads was termed an “illuminated theater of American commerce” in one history. And in 1948 one Times Square billboard ventured for theatricality in a way that caught the attention of the editors of LIFE magazine—whose offices were only a few blocks away.

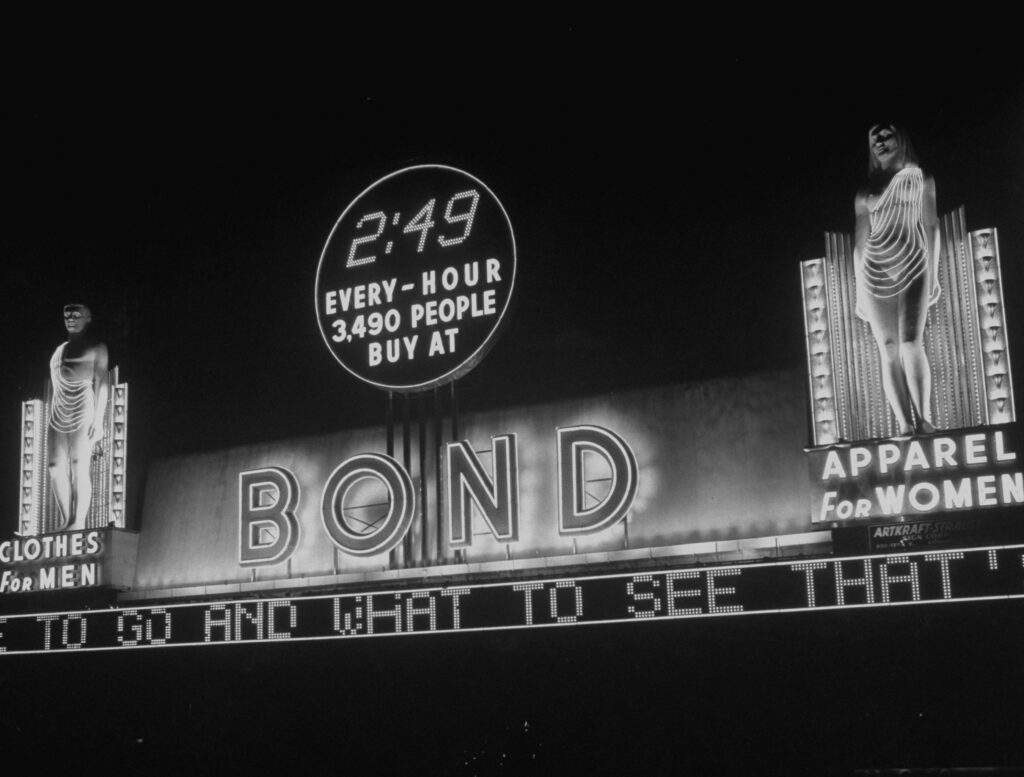

The billboard promoted Bond Clothing, which was a major men’s retailer of that era and operated a store in Times Square from 1940 to 1977.

LIFE magazine’s story about it was headlined “New Spectacular.” (Back then the term “spectacular” referred to billboards that had an extra level of showmanship. The most famous example might be the cigar billboard that blew smoke rings.)

Here’s how the magazine described the arrival of the new Bond Clothing spectacular:

Last week the Square got its biggest and strangest sign—a hugely anatomical atrocity mounted on the roof of a block-long Bond clothing store. The sign’s most notable features: a waterfall 132 feet wide and figures of a man and a woman, each five stories high. The statues were draped only in 175 yards of neon tubing.

While claiming to be aghast at the “atrocity,” LIFE nonetheless ran seven photos of it in the magazine, tracking the giant figures from their construction to their installation in Times Square.

Looking at the photos taken by Martha Holmes, it’s hard not to appreciate the curiosity value. Whether it’s the image of a craftsman nonchalantly smoothing the surface of the giant breasts, or passers by in Times Square gawking at these massive pieces of shaped cement, the effect is an eye-catching mix of the surreal and the juvenile. It all brings to mind Julia Roberts’ musings about men’s anatomical fixations in the movie Notting Hill.

The photo which best captures the spirit of the moment is the shot of two women in overcoats posing next to the breasts, giddy smiles on their faces.

Back then it was Martha Holmes taking the photos. Were pieces of statuary like this set out in Times Square today, the number of selfies taken would be incalculable.

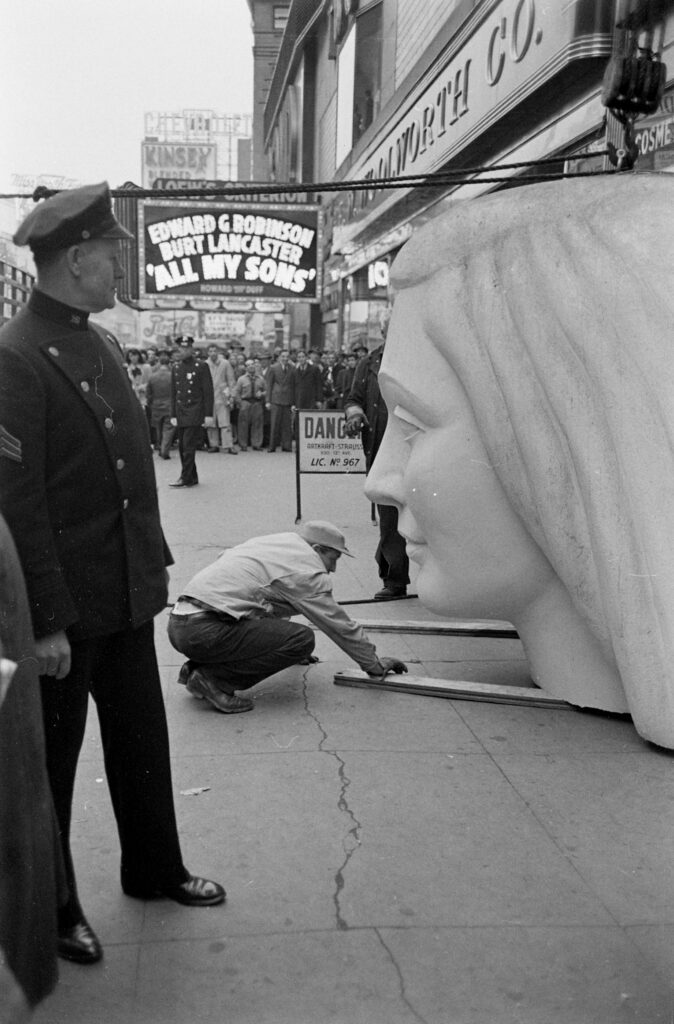

The heads of the figures that were going to be part of a Times Square display weighed about 600 pounds each, 1948.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

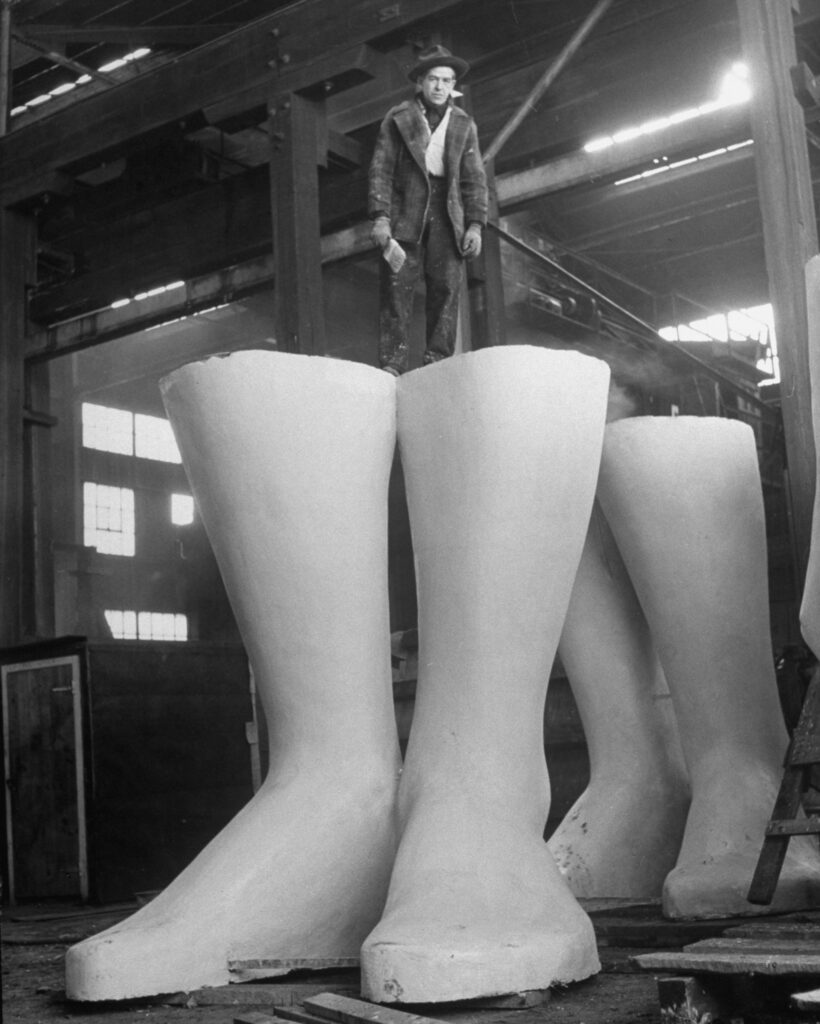

A man stood atop pieces of a giant statue about to be displayed in Times Square as an advertisement for Bond Clothing, 1948.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

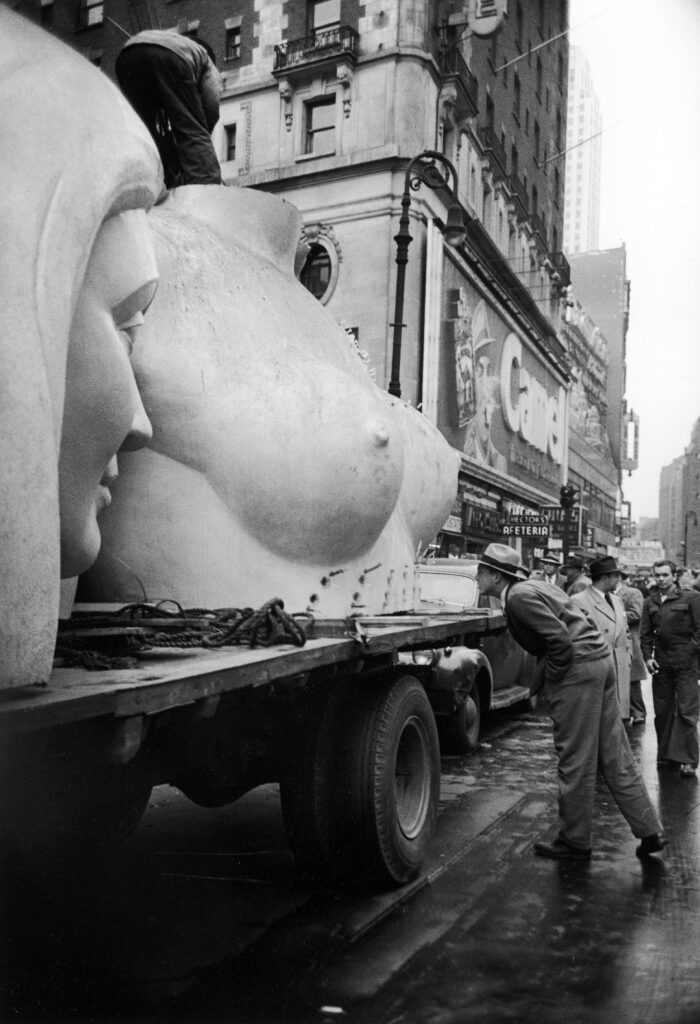

An artisan worked on part of an advertising display for Bond Clothing that was about to go into place in Times Square, 1948.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Parts of a giant display in Times Square awaited their deployment, 1948.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Women posed alongside a part of a sculpture that was soon to be lifted into place in Times Square as part of a display for Bond Clothing, 1948.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

This giant head was set to be part of a Times Square display for Bond Clothing, 1948.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

A man examined a sculpted pair of breasts, which sat next to an enormous head on a flatbed trailer in Times Square, New York, May 1948. The pieces were part of a building-mounted advertising campaign for Bond Clothing.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Pieces of an advertising display for Bond Clothing were lifted into place in Times Square, 1948.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

People in Times Square watch as pieces of a giant display for Bond Clothing are about to be lifted into place, 1948.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Pieces of an advertising display for Bond Clothing were lifted into place in Times Square, 1948.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Pieces of an advertising display for Bond Clothing were lifted into place in Times Square, 1948.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

An enormous billboard display for Bond Clothing started to come together in Times Square, 1948.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Giant figures draped in neon were part of a Times Square display for Bond Clothing, 1948.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock