The assignment for Dmitri Kessel was a straightforward one: capture images of Italy getting back to normal after World War II. His photos were part of a larger package showing how the Marshall Plan was helping to rebuild Europe.

LIFE wrote in its 1948 report that, after the brutal war years, Europe was seeing a revival:

From the tip of Italy north to Scapa Flow, American travelers are discovering a surprising new look on the war-scarred face of Western Europe. Buildings are going up, the railroads are running, there is more food and the trade is brisk. In many small Italian villages newly painted homes gleam amidst the old colors of yellow terra cotta…. To Americans, who for a decade have only heard reports of European misery, all this comes as a pleasant shock.

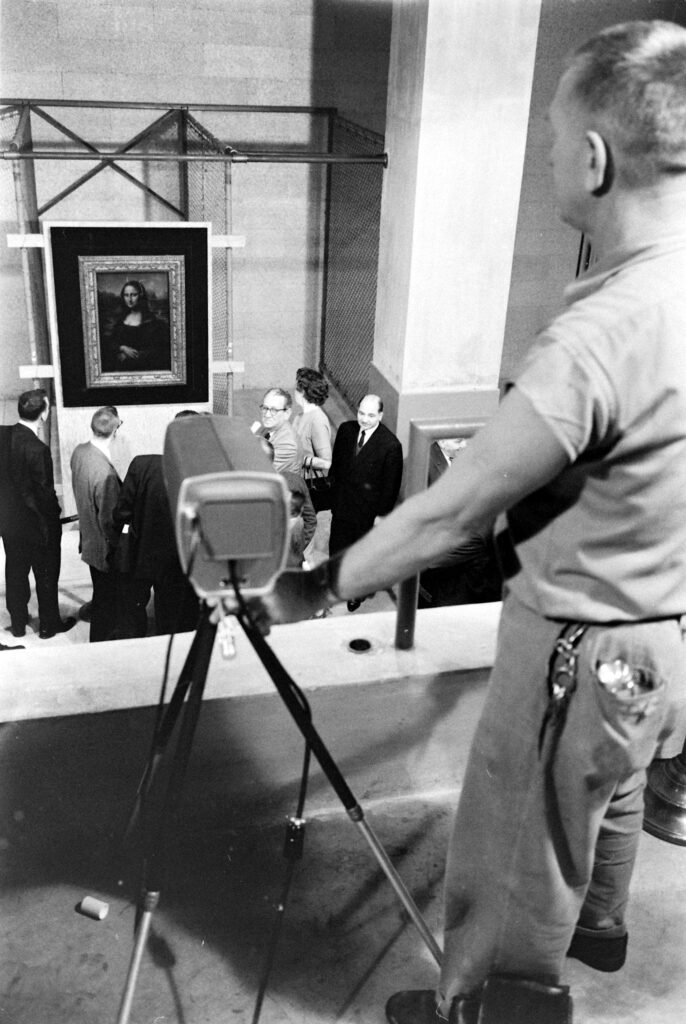

To document this moment of change, Kessel took photos of people enjoying a beach that had been previously unusable because it had been planted with land mines. He showed men working at an Alfa Romeo factory in Milan that had been bombed in 1944, but was nearing its old production levels. Kessel also showed tourists from India and the United States visiting attractions that draw people the world over.

Kessel was not the first LIFE photographer to undertake an assignment like this. The year before, in 1947, Alfred Eisenstadt had also gone to Italy to survey the country’s post-war progress and come home with his own collection of amazing images.

While the scars of World War II were still fresh—one of Kessel’s photos shows workers rebuilding a bridge that had been taken out during the fighting—the country remained photogenic. It’s why LIFE photographers—and tourists (including 60 million in 2024)—keep making Italy one of the most visited countries in the world.

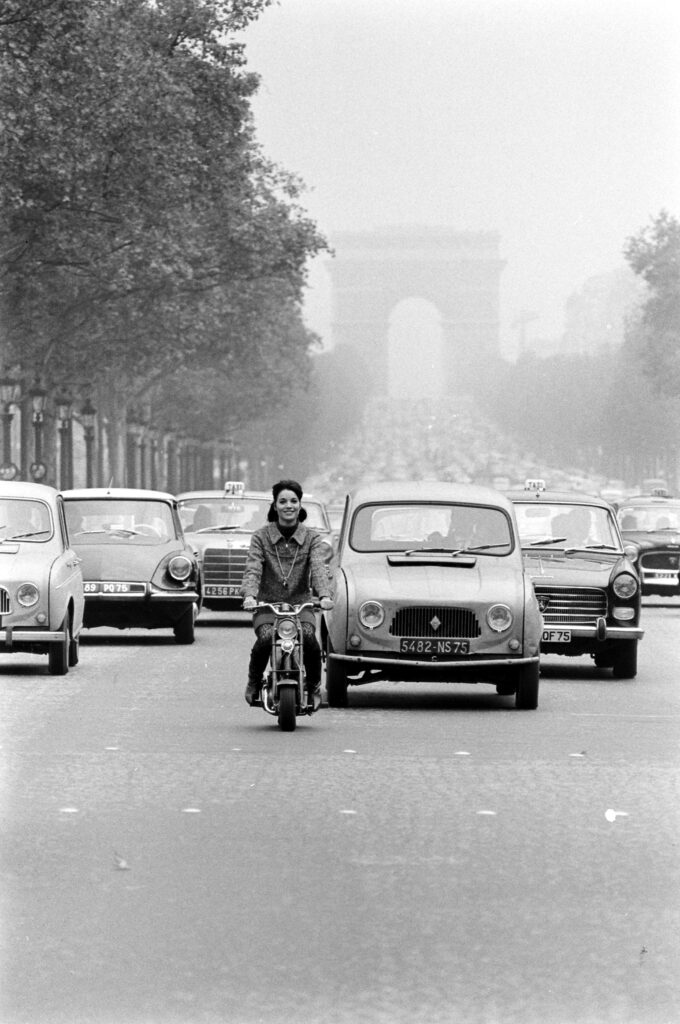

Scenes around Italy from a story about the country starting to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

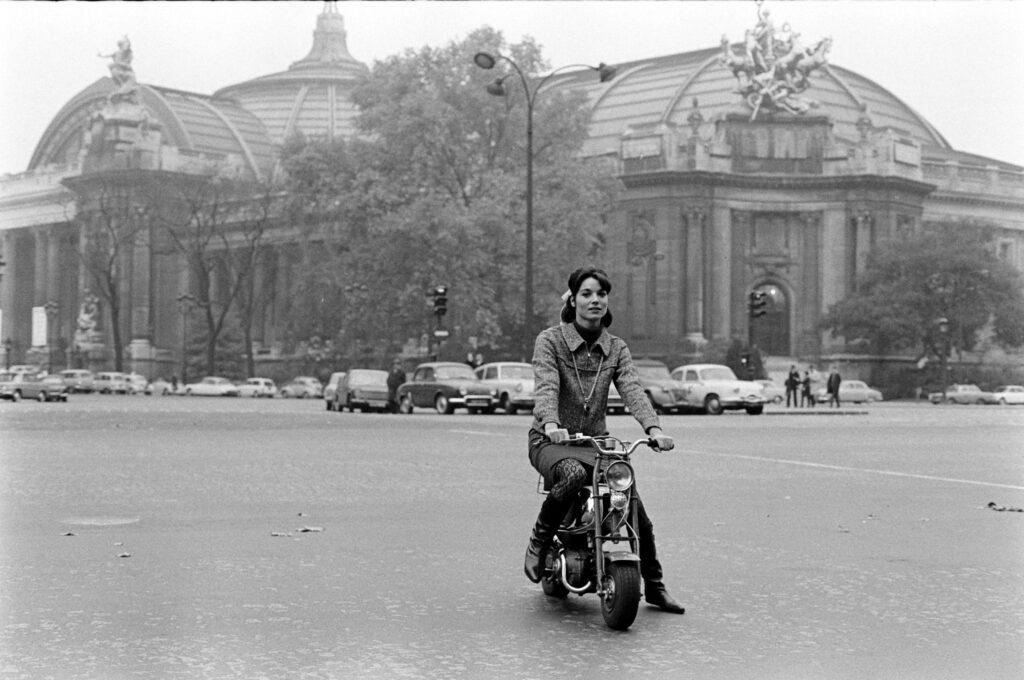

Scenes around Italy from a story about the country starting to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

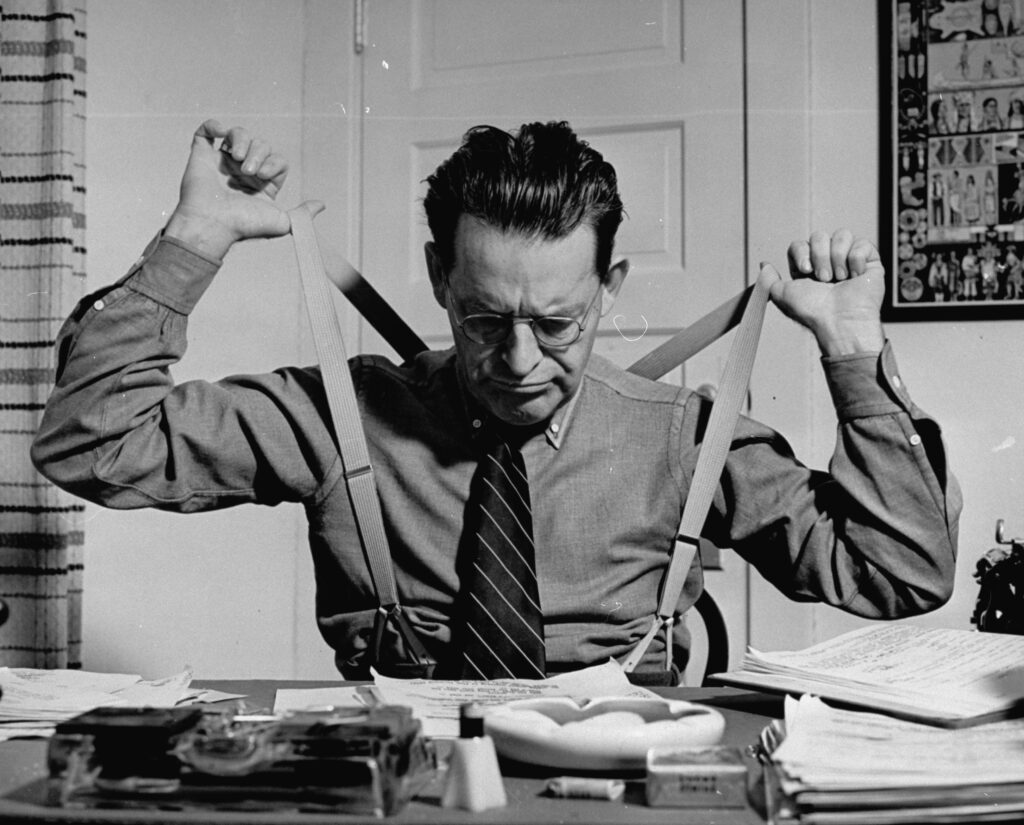

Scenes around Italy from a story about the country starting to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

This Italian beach, which had been planted with landmines during World War II, was now safe for public use, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

People danced on the terrace of an Italian beach as the country began to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

A man and woman conversed at an Italian beach, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Scenes around Italy from a story about the country starting to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Scenes around Italy from a story about the country starting to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Scenes around Italy from a story about the country starting to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

People in Rome sunbathed and swawm at the Tiber boathouse, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Men played checkers by the water in Italy, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

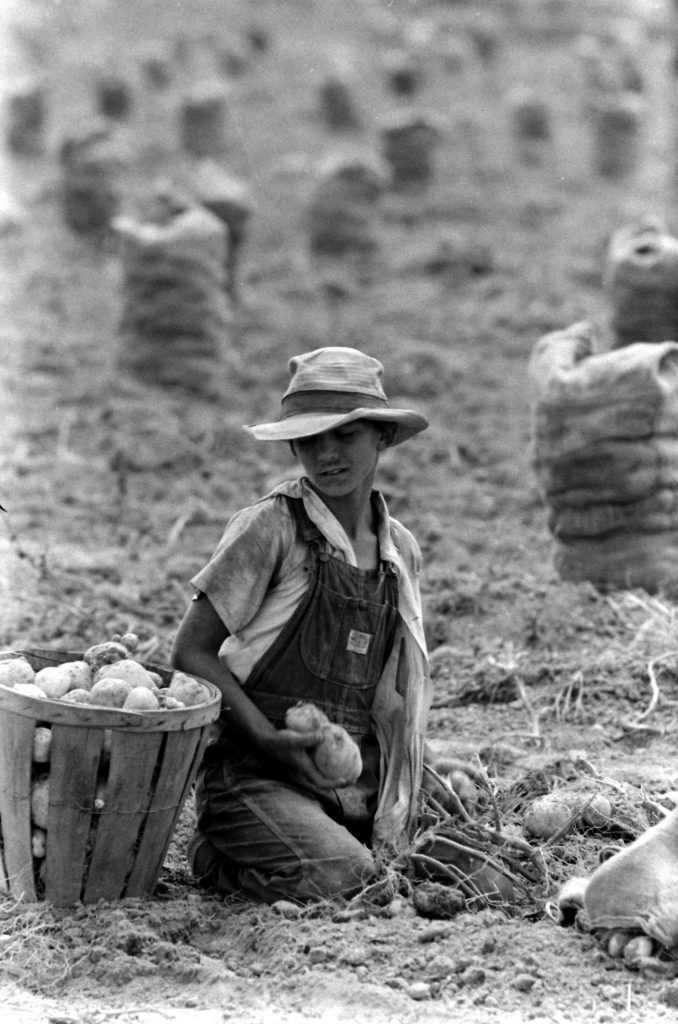

Scenes around Italy from a story about the country starting to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

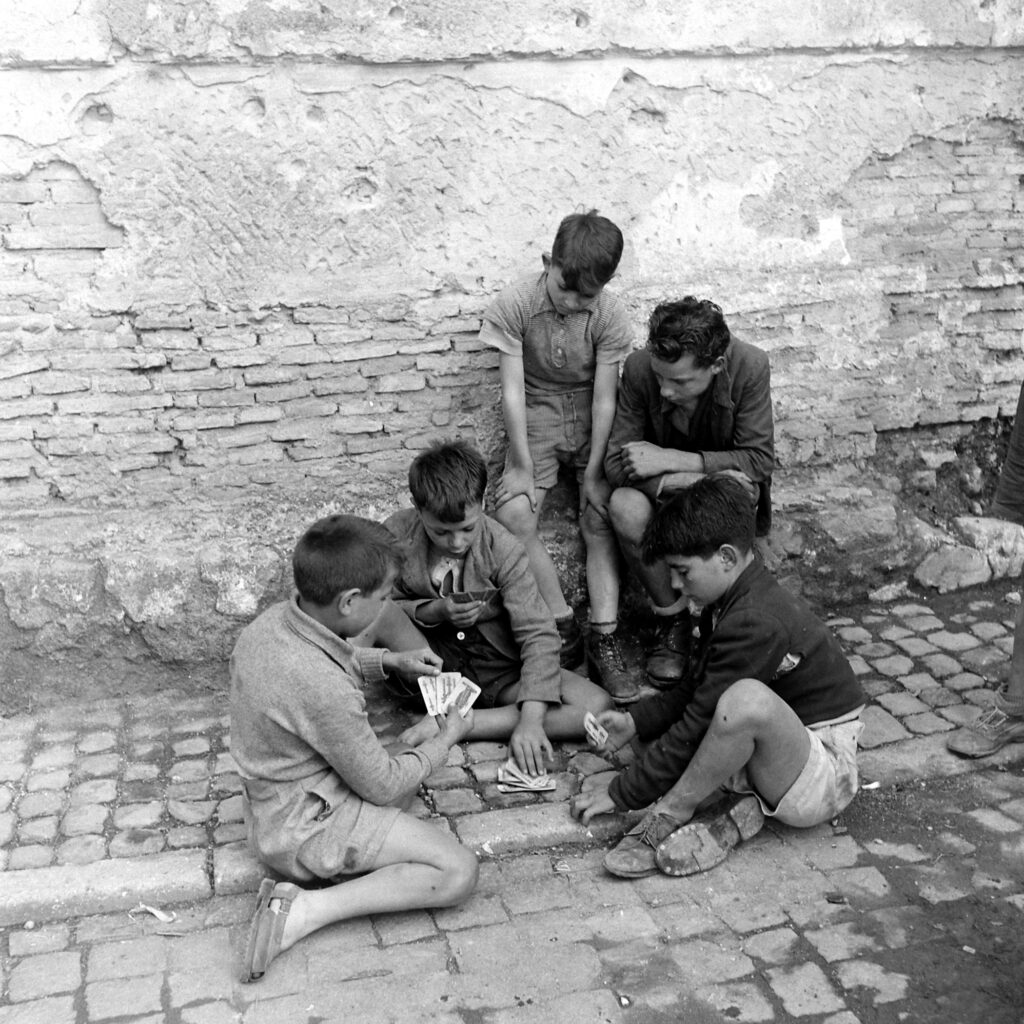

Children played cards on the street in Italy, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

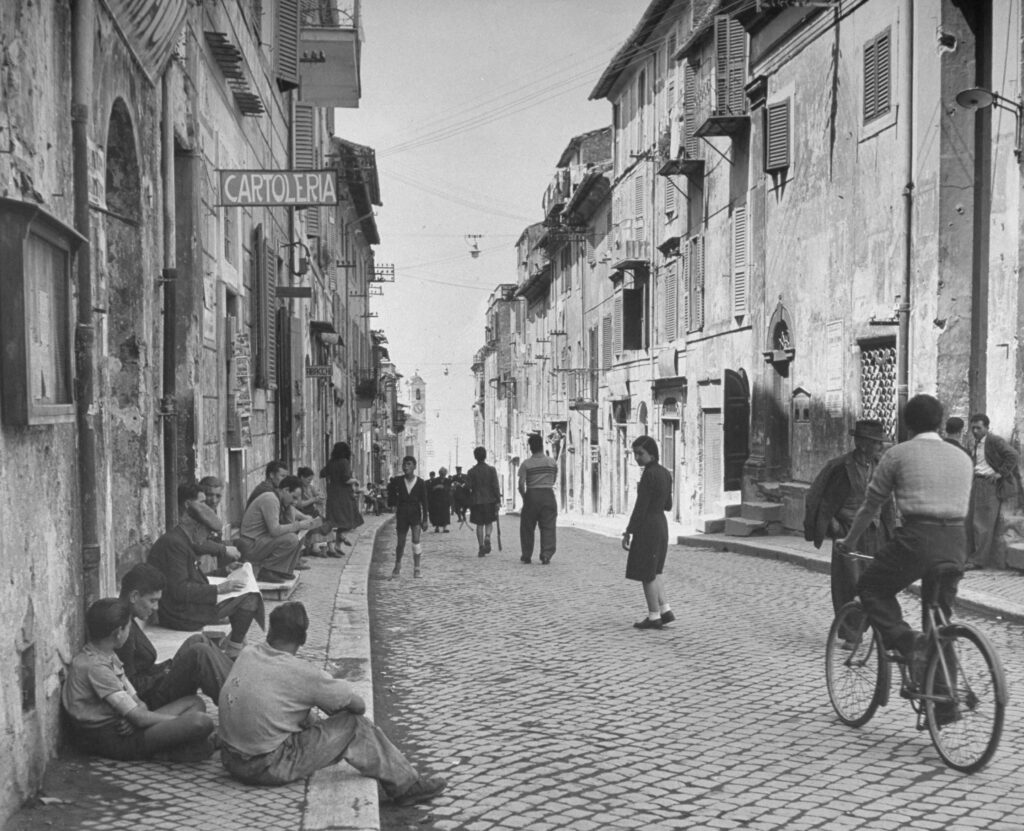

Scenes around Italy from a story about the country starting to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

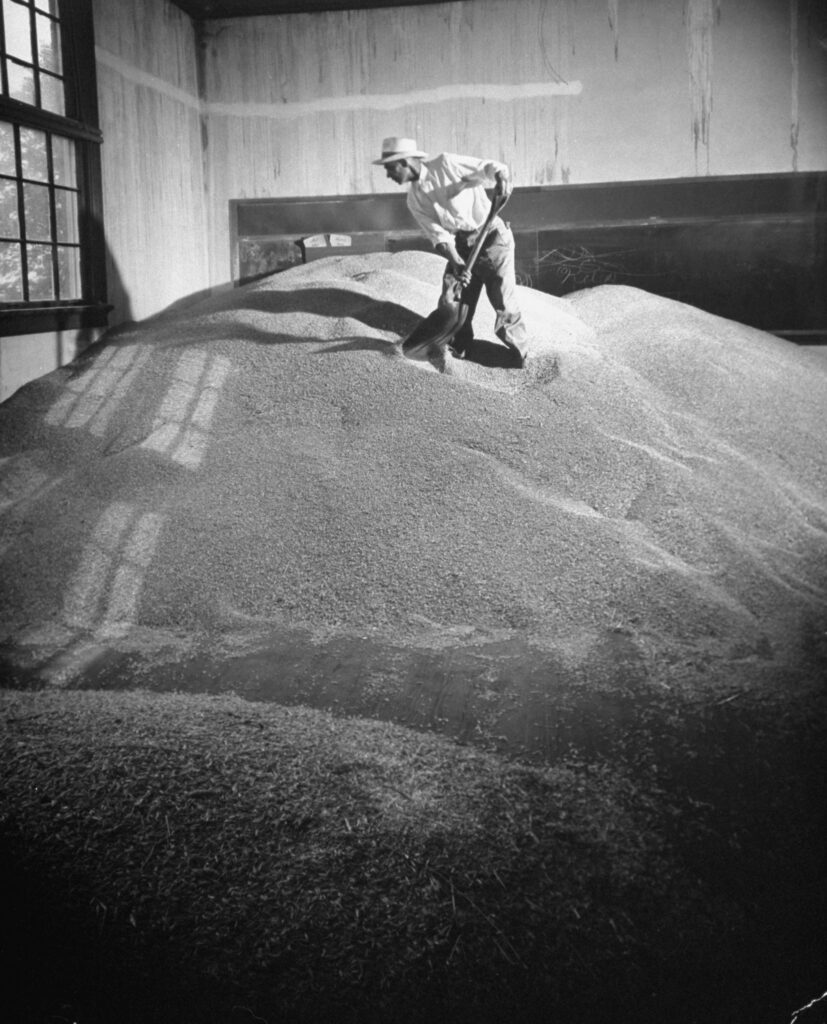

People harvested grain in Italy, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

A team of four oxen pulled a harvester over an oat field in Italy, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

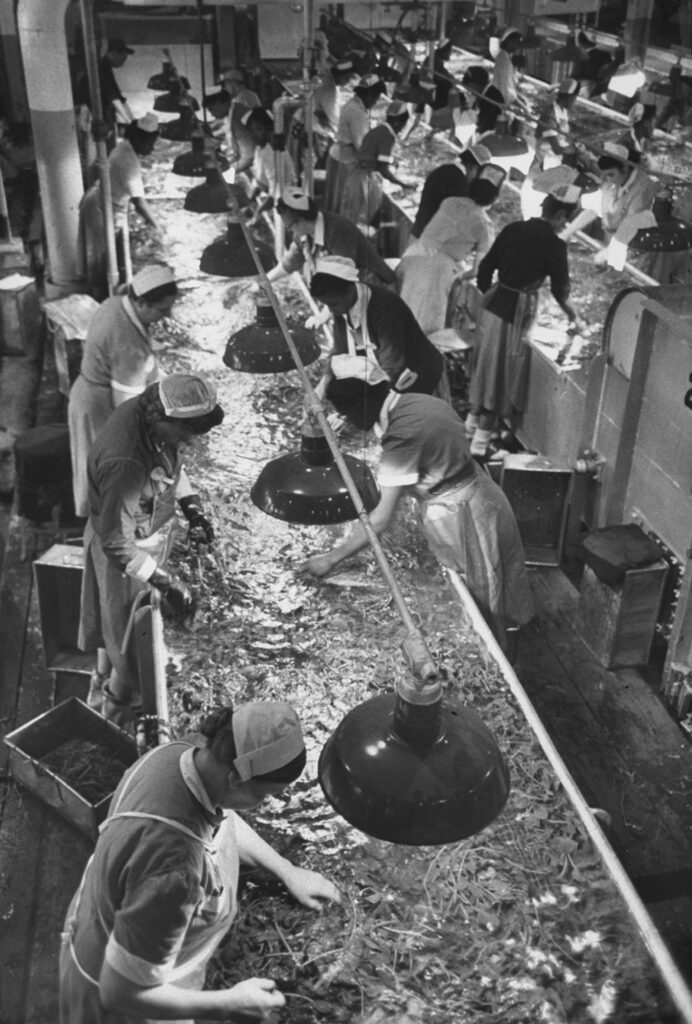

Factory workers in Italy, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

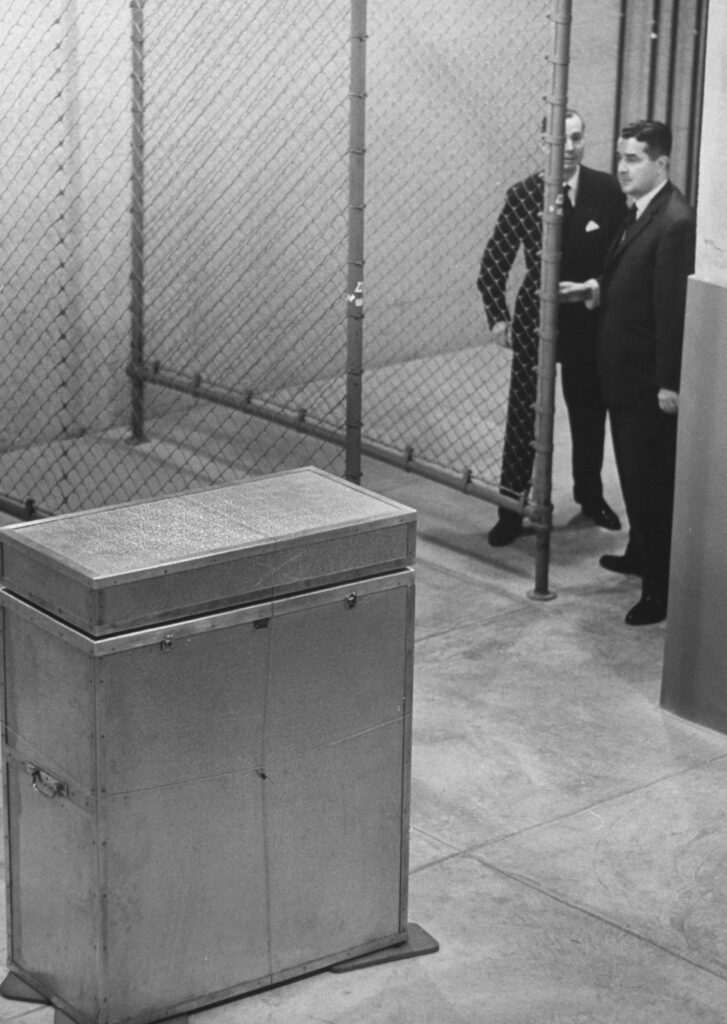

The Alfa Romeo plant in Milan, Italy, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

The Alfa Romeo plant in Milan, Italy, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Two newly assembled Alfa Romeos were checked over at the company factory in Milan, Italy, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

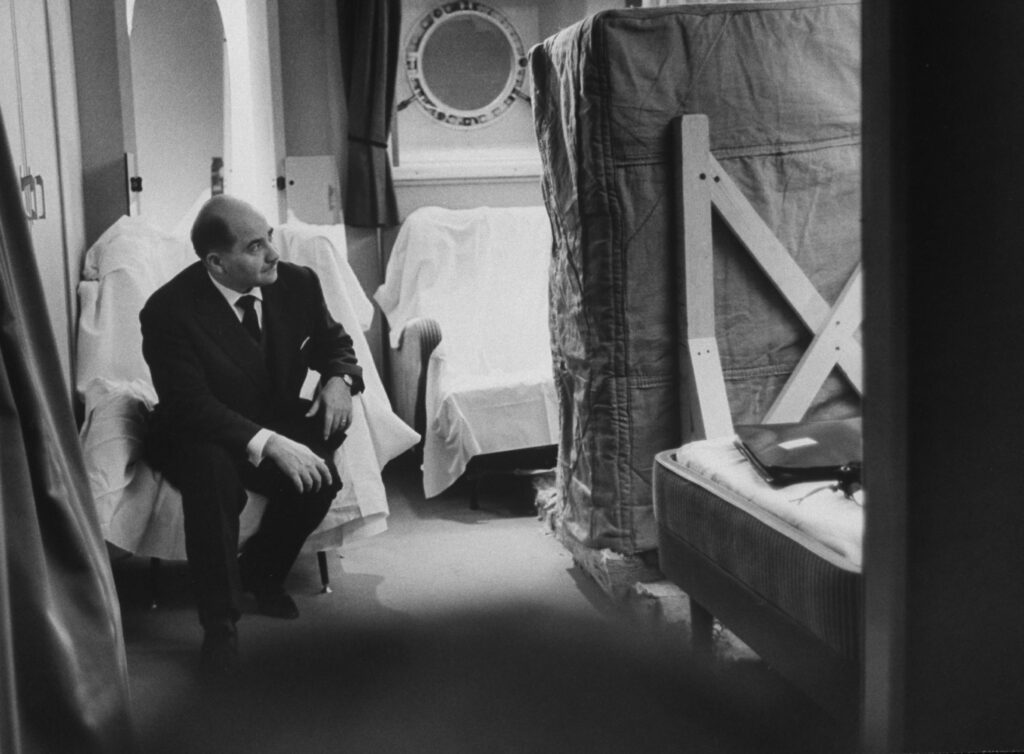

Scenes around Italy from a story about the country starting to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

American sightseers at St. Peter’s in Rome, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Tourists posed at the Colosseum in Rome, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

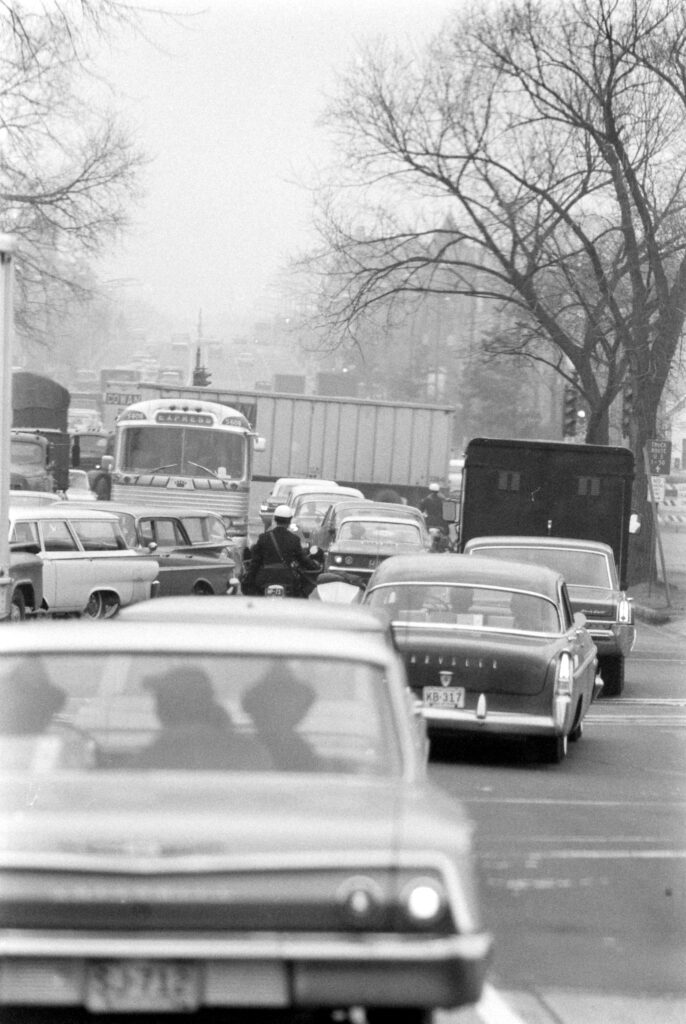

Scenes around Italy from a story about the country starting to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Scenes around Italy from a story about the country starting to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Workers reconstructed a bridge over the Po River as Italy began to bounce back from World War II, 1948.

Dmitri Kessel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock