When the play The Green Pastures debuted on the stage on February 26,1930, it was more than a groundbreaker. Not only was it the first Broadway show with an all-Black cast, but it won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama and was so successful that the show ran for a year and a half, until August 29, 1931. After that the show toured the country, playing in all but eight U.S. states before coming back to Broadway in 1935.

LIFE, which published its first issue in 1936, wasn’t around for that original performance. But it was able to shine a spotlight on The Green Pastures during a 1951 revival, with staff photographer W. Eugene Smith documenting the action.

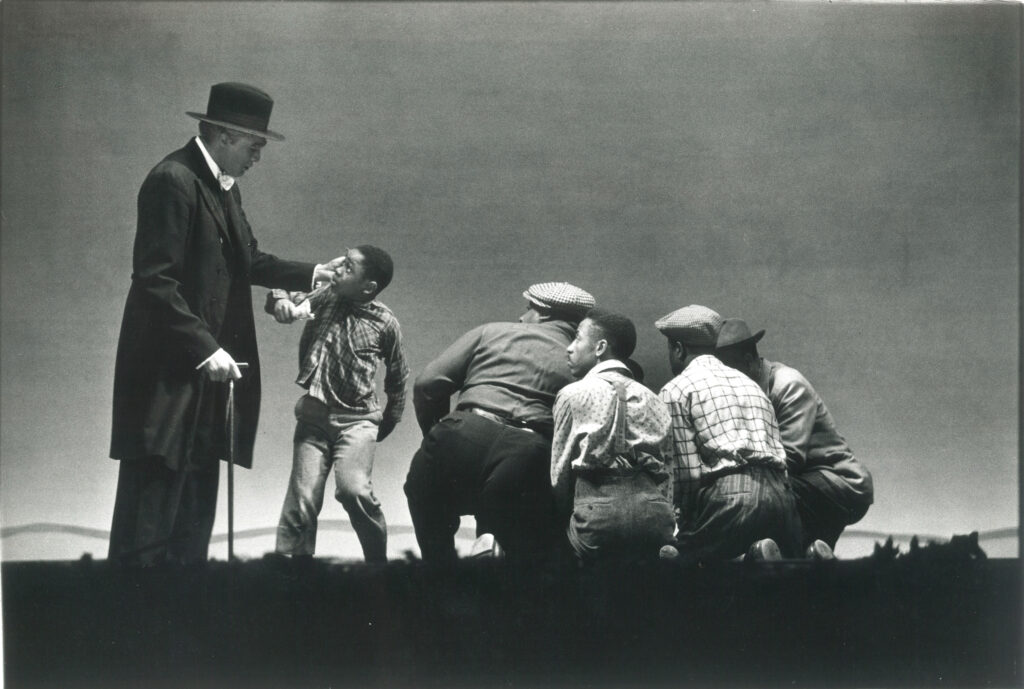

The play, adapted from a 1928 book Ol’ Man Adam an’ his Chillun by Roark Bradford, features stories of the Hebrew bible as told by a young Black child in the South. The central character of the play is De Lawd, who in the 1951 production was played by William Marshall, a deep-voiced 6’5″ actor whose long career on stage and screen would include many productions of Shakespeare’s Othello—and also the title role in the 1973 blaxploitation film Blacula.

LIFE’s opening of its 1951 story about The Green Pastures gives some of the flavor of the show:

Once again on Broadway the curtain went up on a heavenly fish fry, and Gabriel shouted, “Gangway for De Lawd…” De Lawd walked among his angels, and tasted a spoonful of custard. “I kin taste de eggs and de creme and de sugar,” he said, and then added, “It needs a little more firmament.” There was no firmament left in the jug so De Lawd passed a miracle to create some. And before you knew it, he had also created the Earth, complete with Adam and Eve.

While the play is historically significant for its casting and won decoration and success, it was not universally loved in its time. Black critics questioned the show’s idealized depiction of the Depression-era rural South for not reflecting the harsh reality of Jim Crow.

And while the show’s original run was a business success, the 1951 revival that LIFE covered was not. While the magazine termed The Green Pastures “a lovable piece of American folklore,” it also noted that ticket sales were weak and the show would close ahead of schedule.

Since that 1951 revival The Green Pastures has not been staged again on Broadway, making the show both a milestone and a relic all at once. LIFE’s headline “Last Glimpse of De Lawd” proved more prescient than the magazine’s editors might have expected.

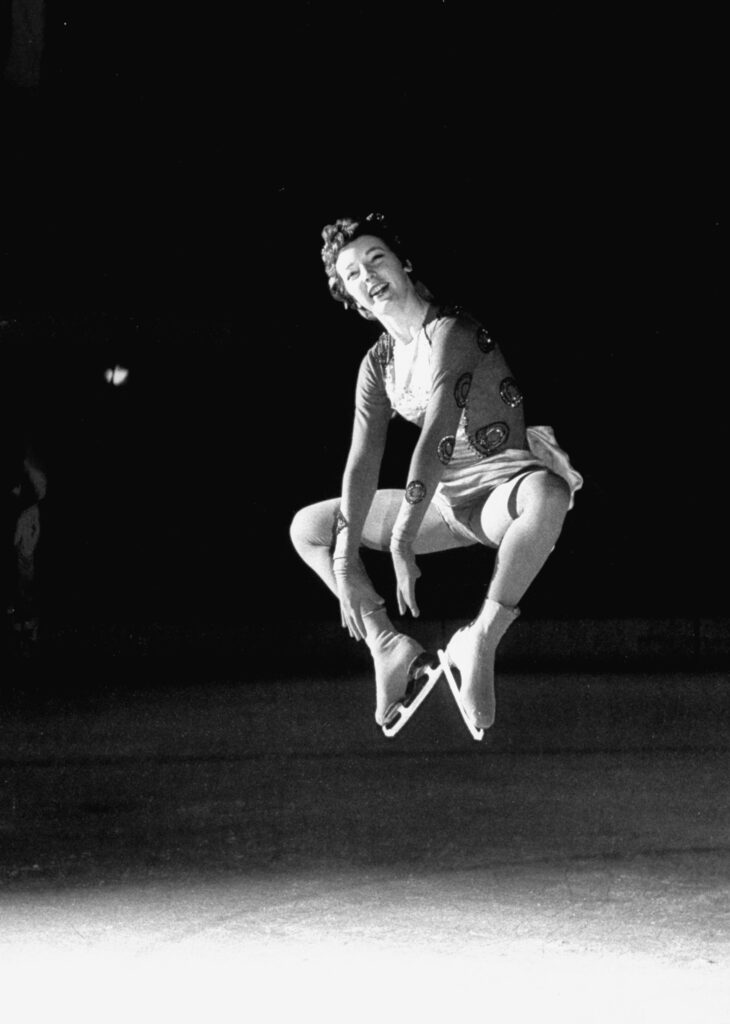

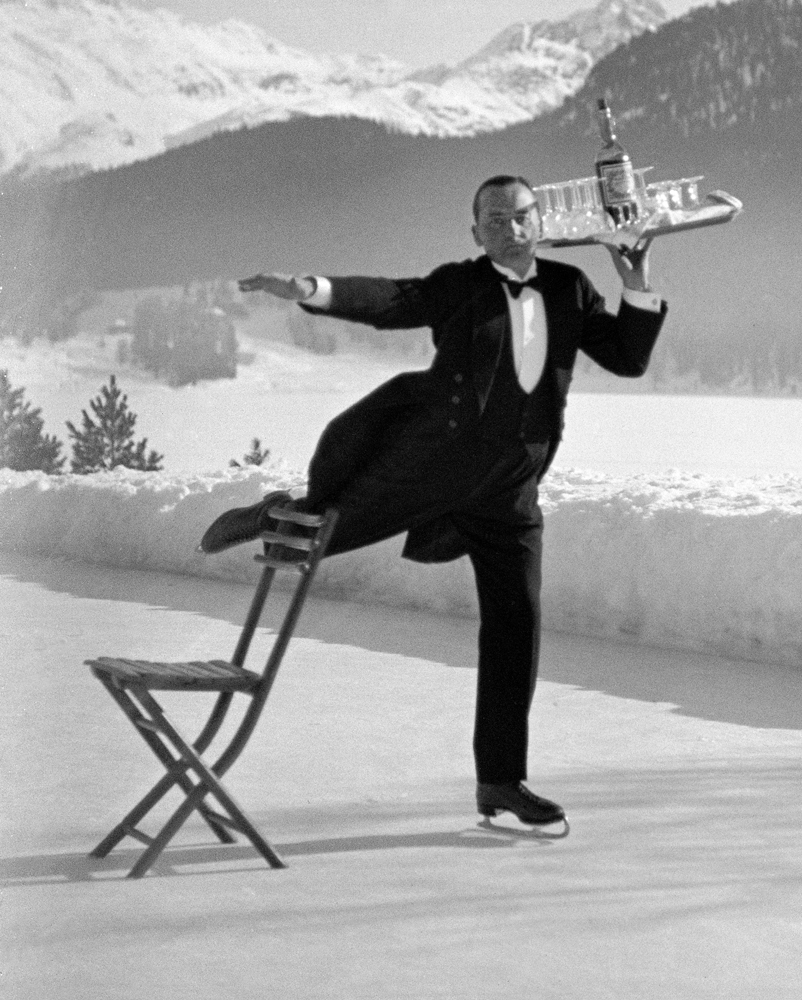

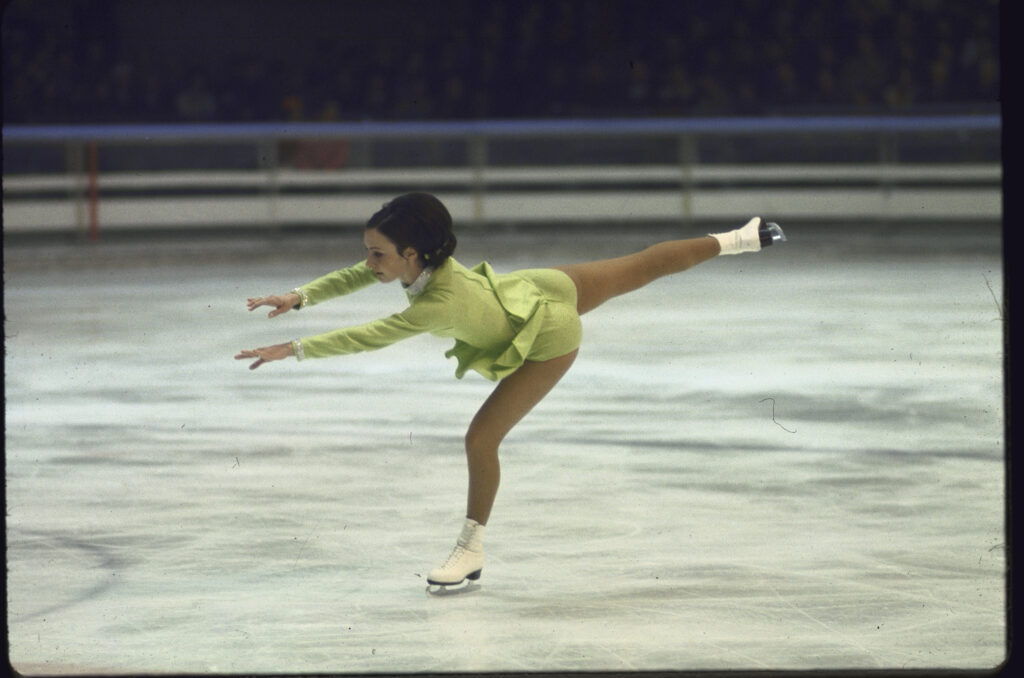

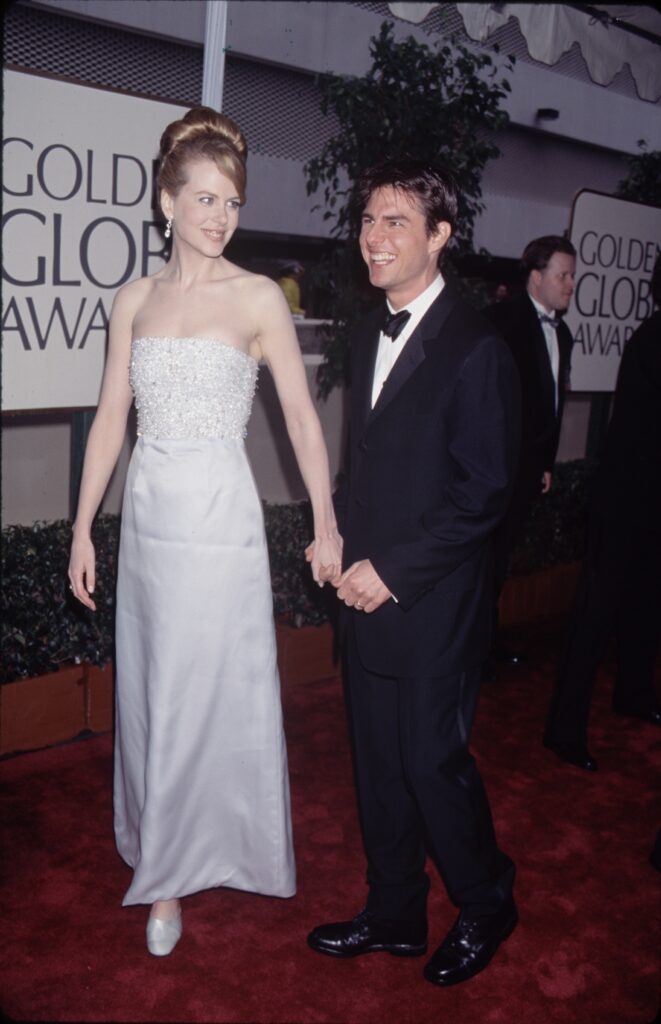

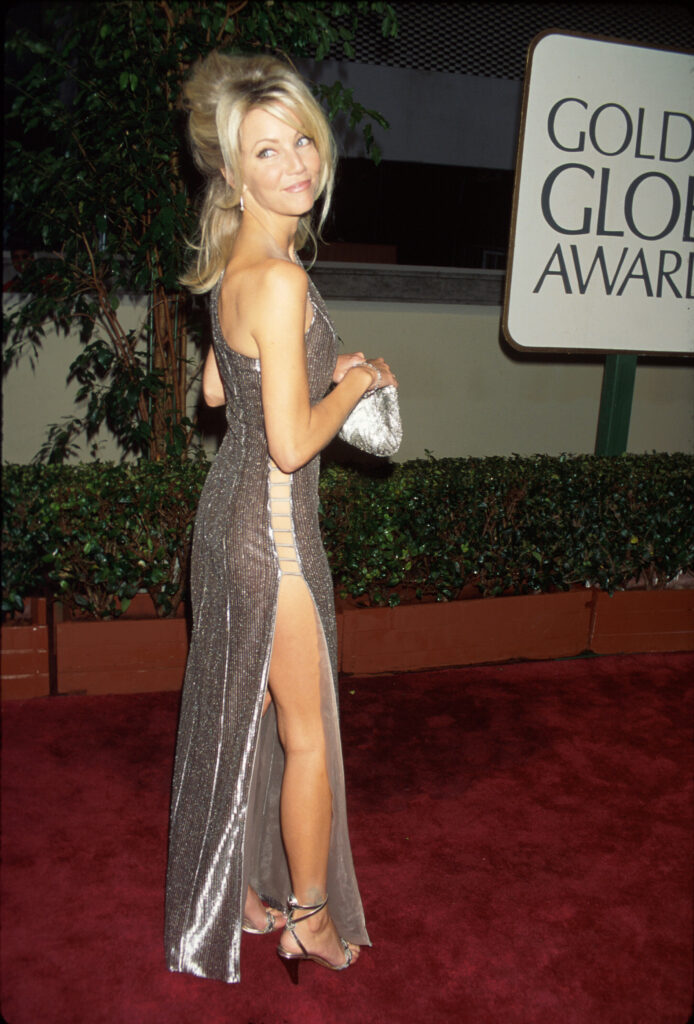

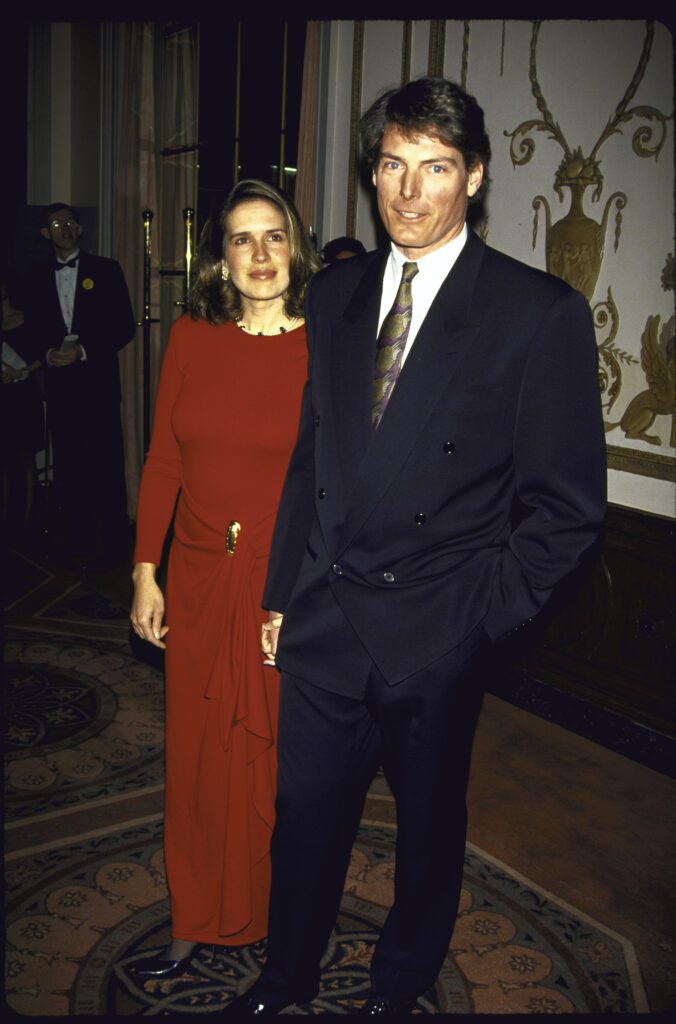

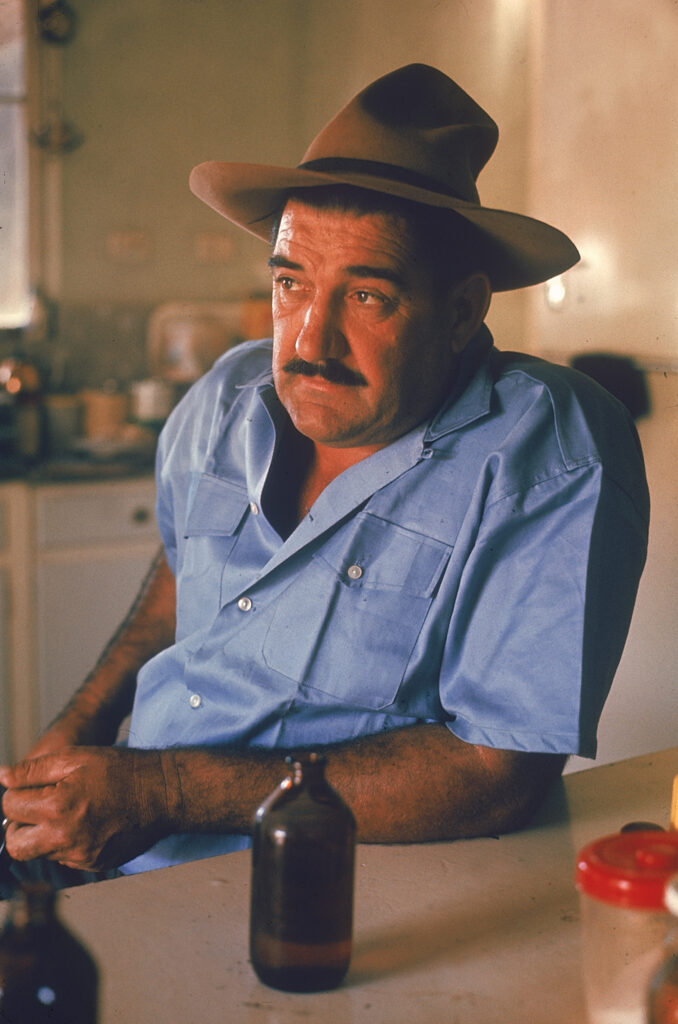

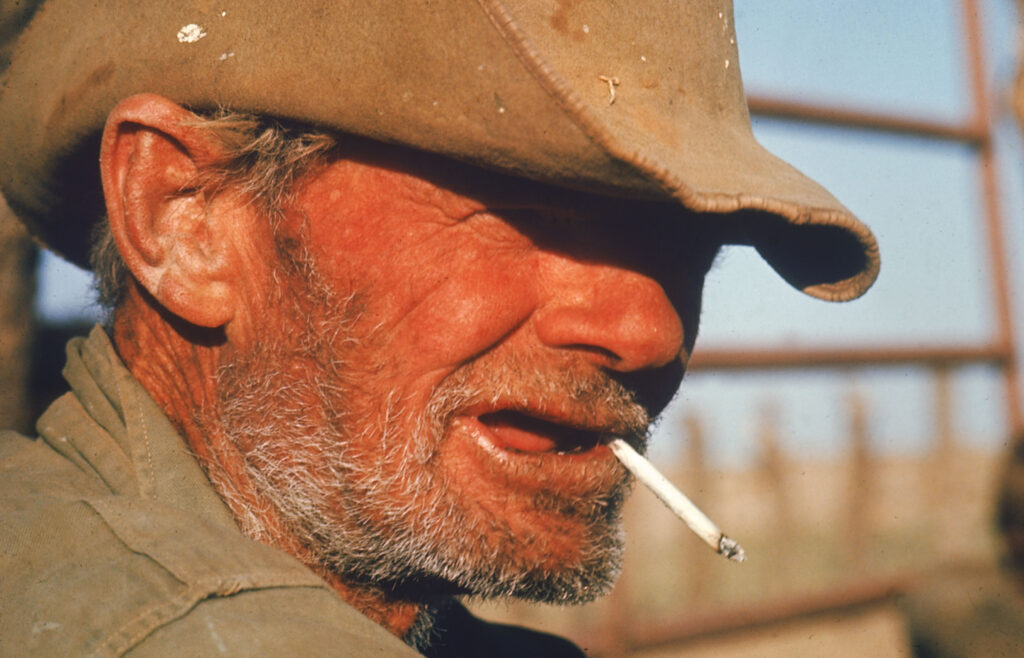

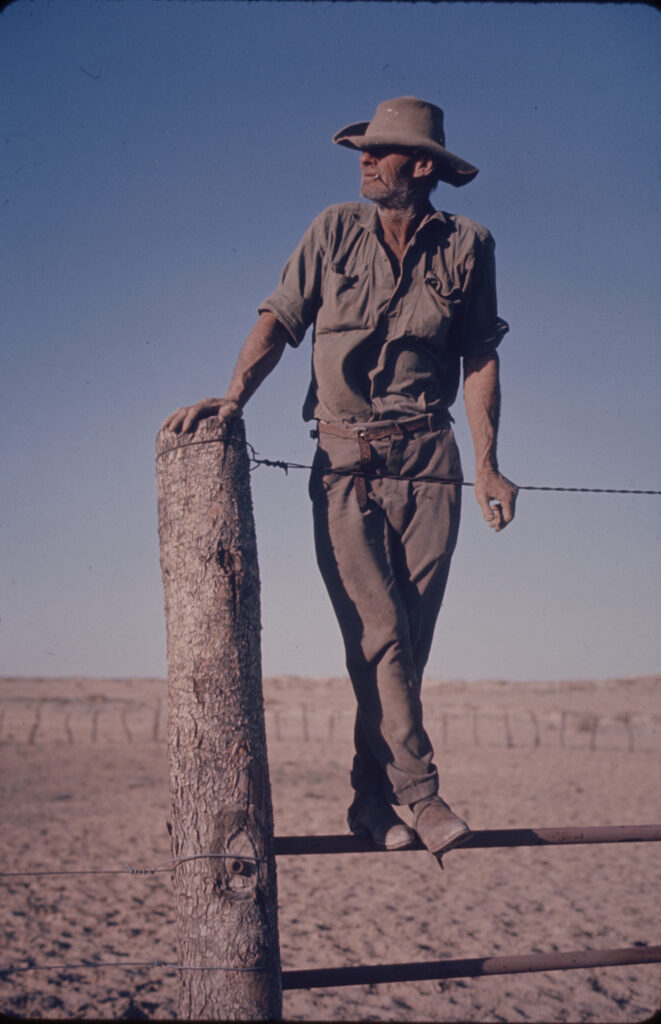

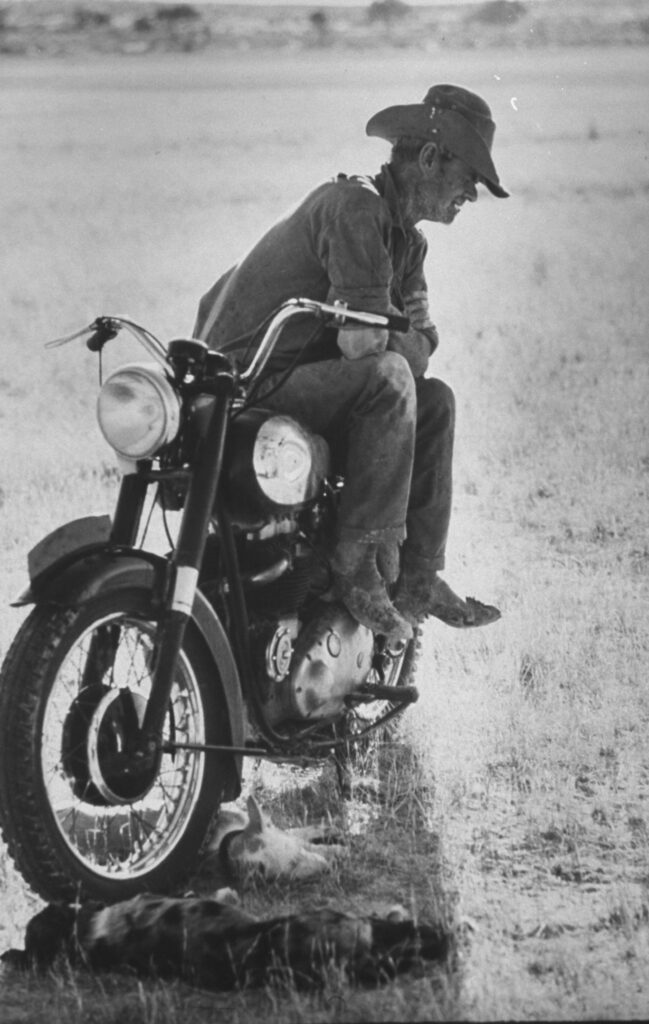

A scene from a 1951 performance of The Green Pastures, which when it debuted in 1930 was the first Broadway show to feature an all-Black cast.

W. Eugene Smith/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

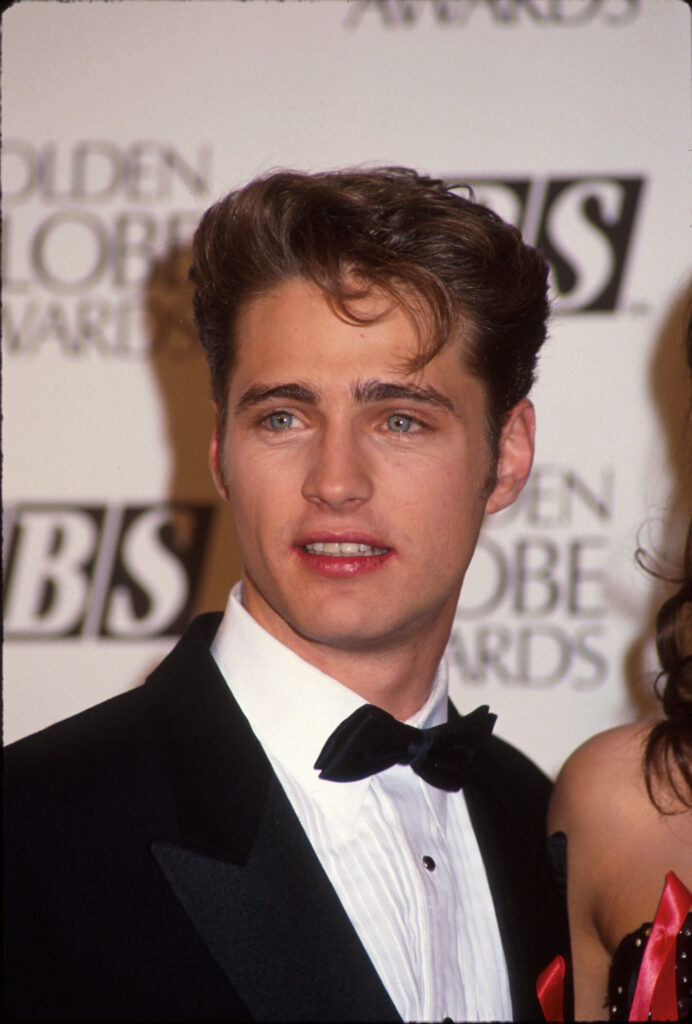

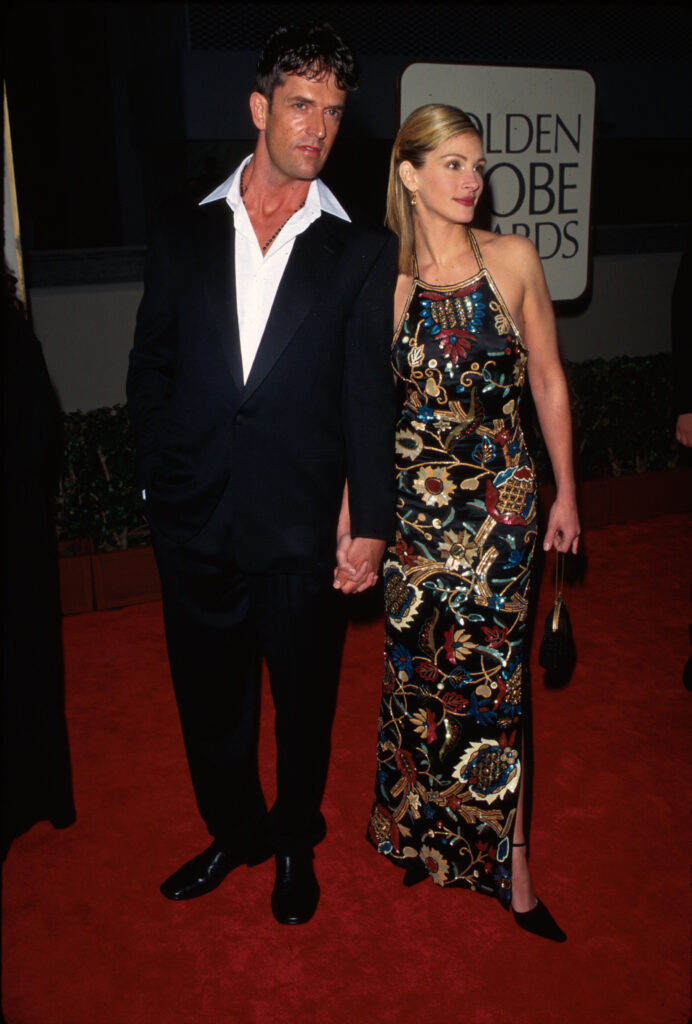

In the play The Green Pastures, De Lawd (played by William Marshall) talks to a child about the evils of playing dice, 1951.

W. Eugene Smith/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

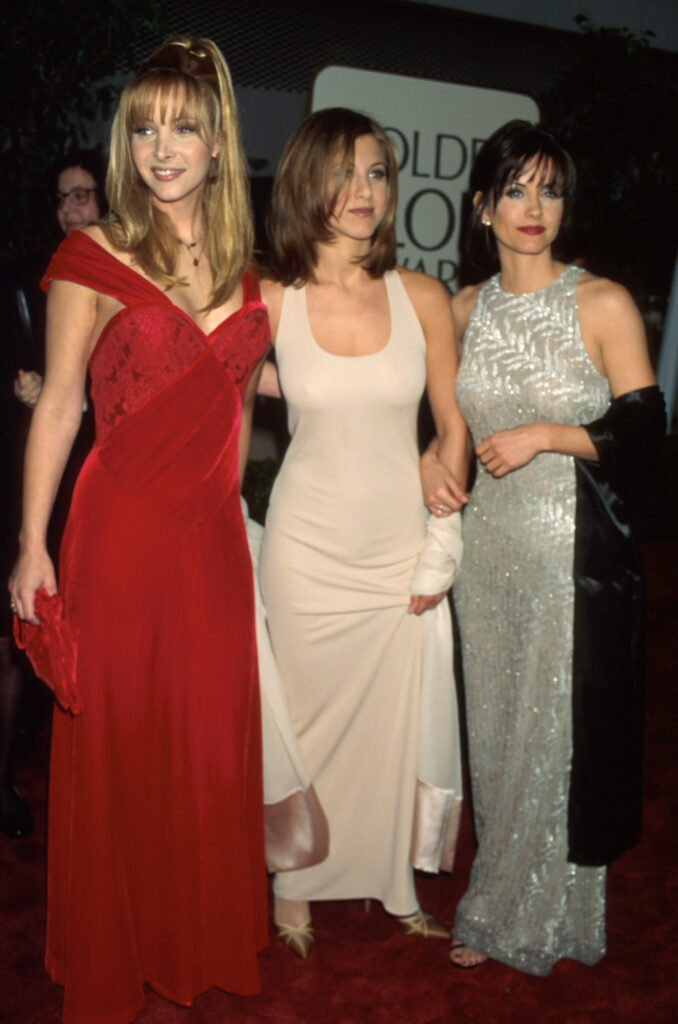

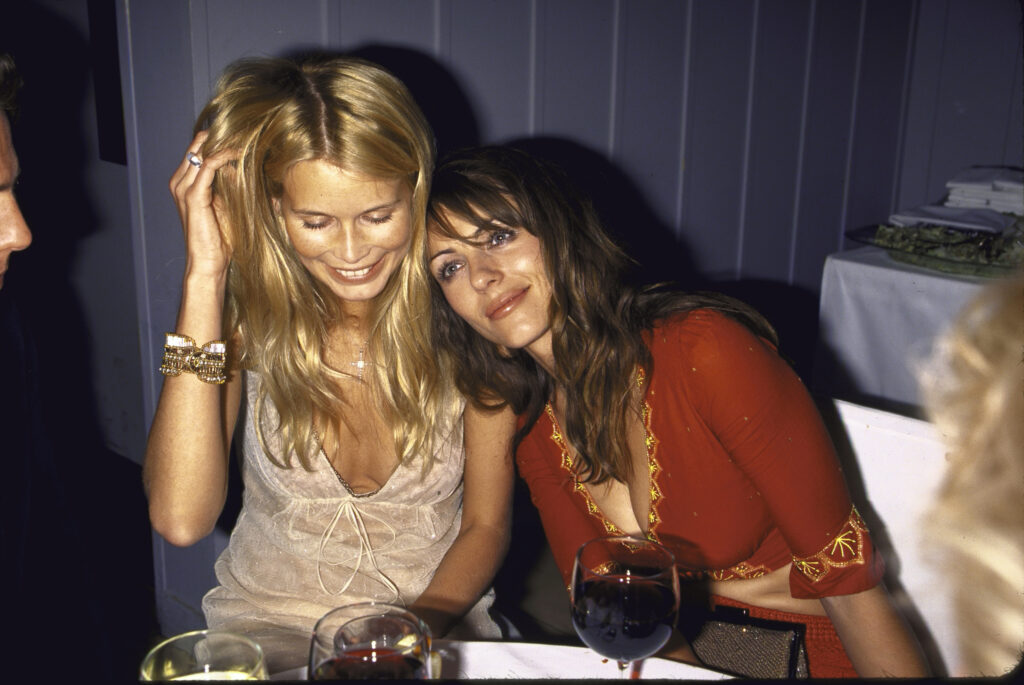

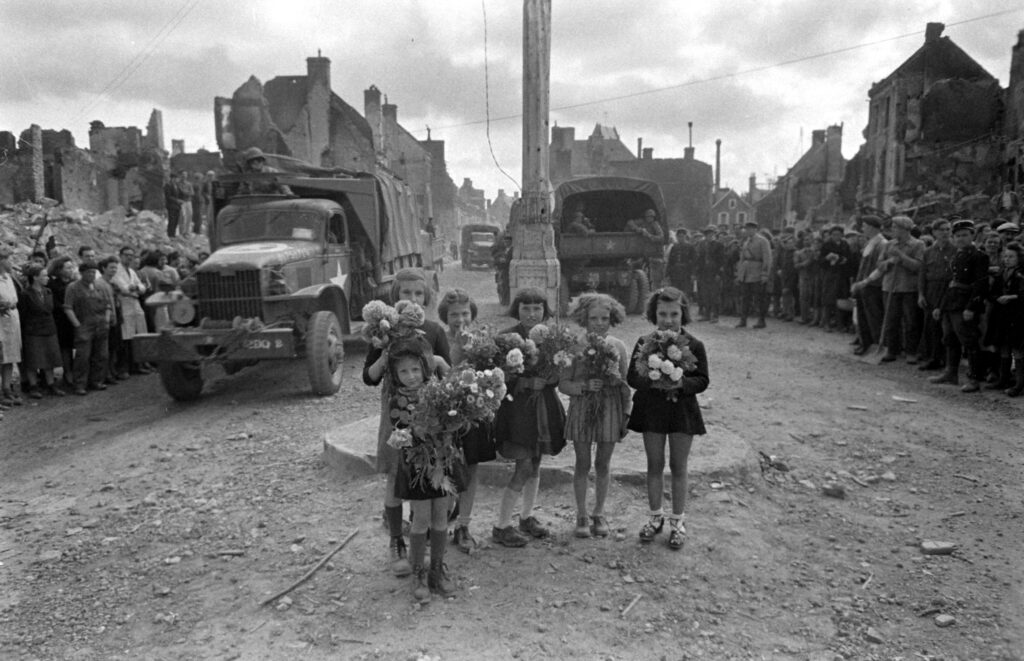

A scene from a 1951 performance of The Green Pastures, which when it debuted in 1930 was the first Broadway show to feature an all-Black cast.

W. Eugene Smith/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

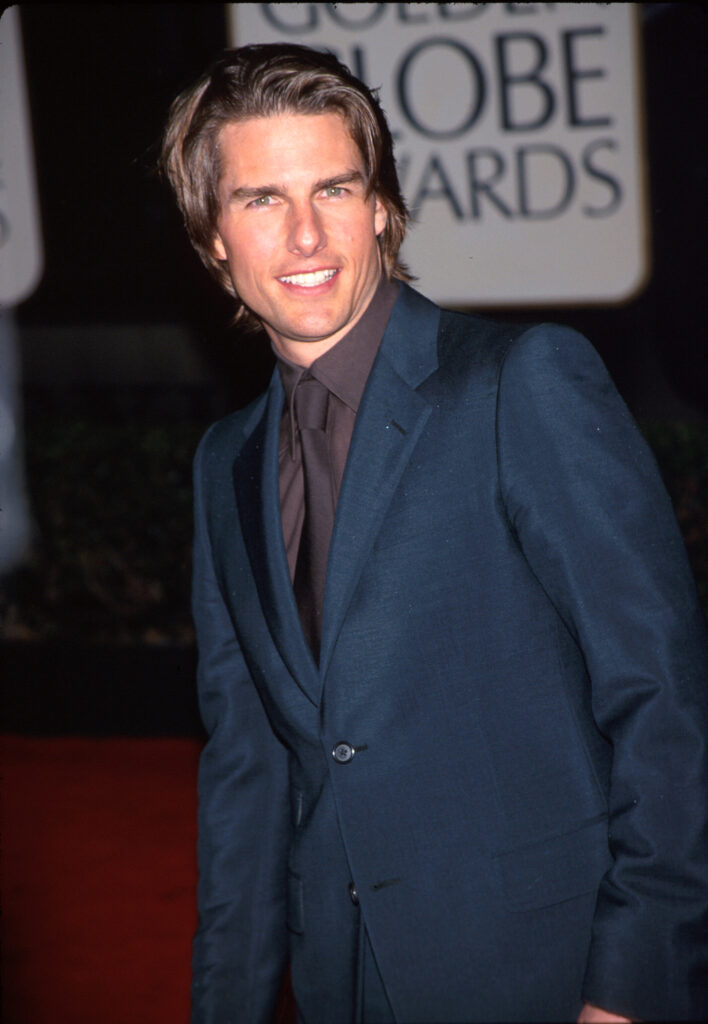

In a scene from the 1951 performance of The Green Pastures, built around stories from the Old Testament, Hebrews march out of Egypt.

W. Eugene Smith/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

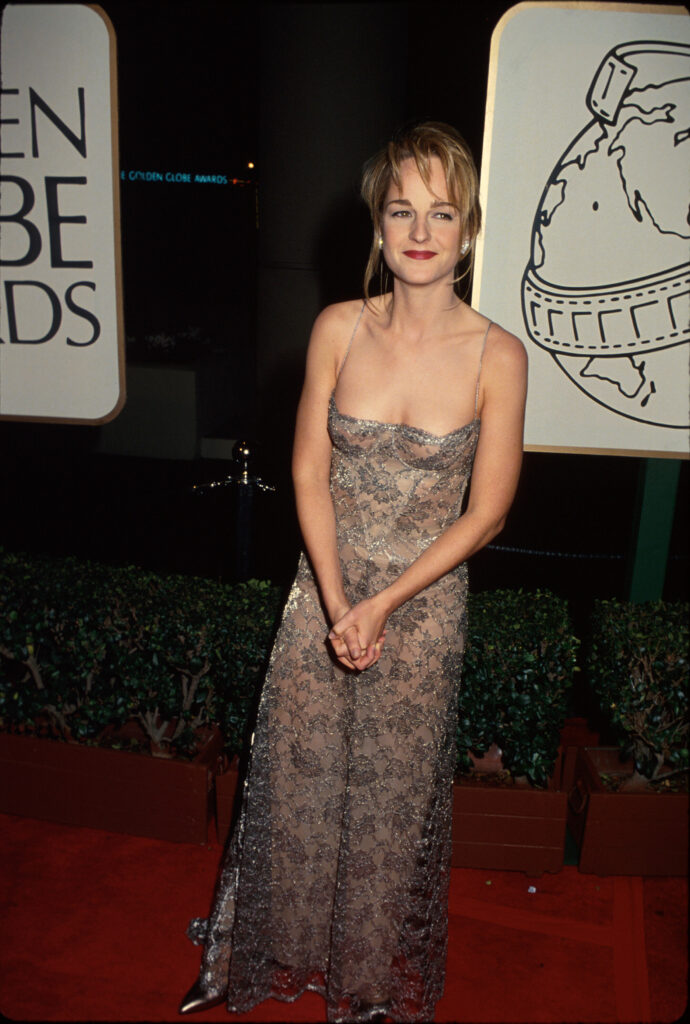

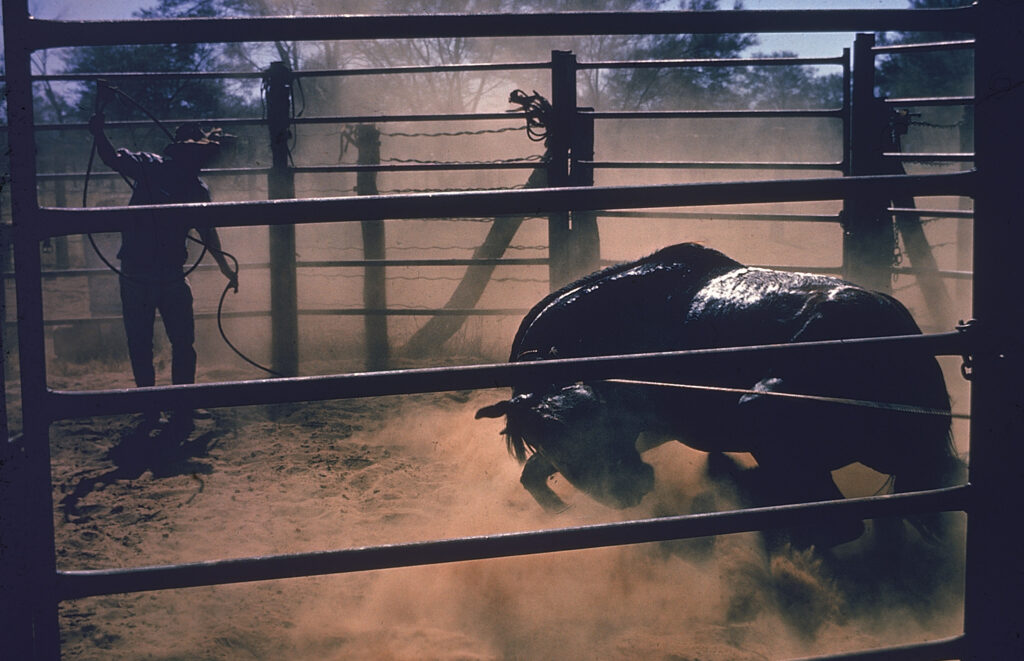

A scene from a 1951 performance of The Green Pastures, which when it debuted in 1930 was the first Broadway show to feature an all-Black cast.

W. Eugene Smith/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

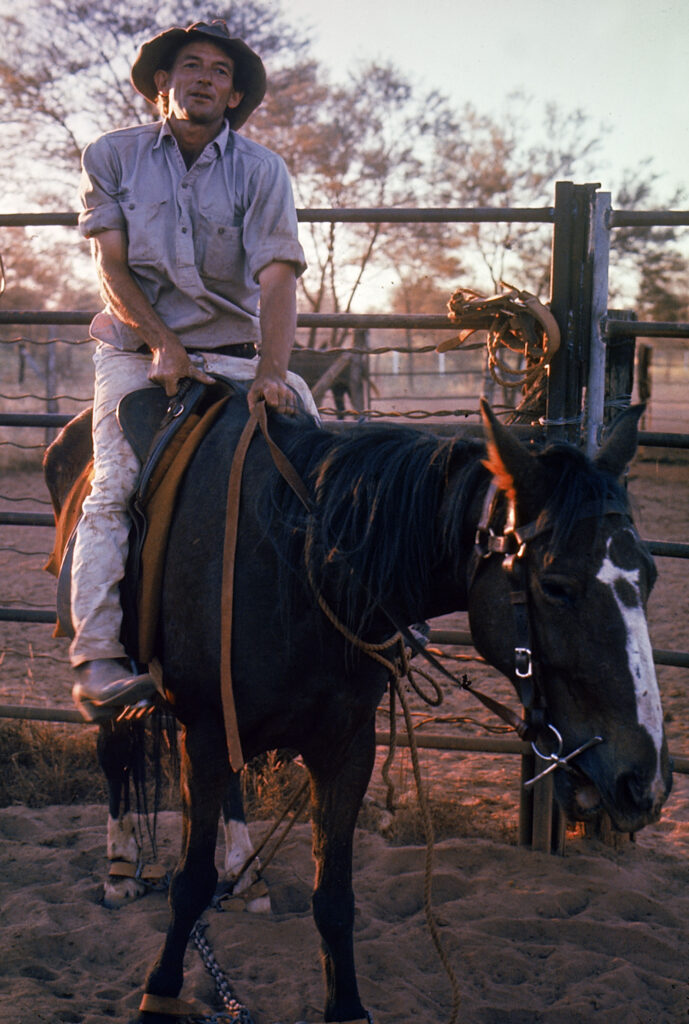

A scene from a 1951 performance of The Green Pastures, which when it debuted in 1930 was the first Broadway show to feature an all-Black cast.

W. Eugene Smith/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

A scene from a 1951 performance of The Green Pastures, which when it debuted in 1930 was the first Broadway show to feature an all-Black cast.

W. Eugene Smith/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

A scene from a 1951 performance of The Green Pastures, which when it debuted in 1930 was the first Broadway show to feature an all-Black cast.

W. Eugene Smith/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

A scene from a 1951 performance of The Green Pastures, which when it debuted in 1930 was the first Broadway show to feature an all-Black cast.

W. Eugene Smith/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock