When the Great Alaska Earthquake convulsed the south-central region of that vast state on March 27, 1964, the energy released by the upheaval— the largest quake in recorded North American history—was, LIFE magazine reported, “400 times the total [energy] of all nuclear bombs ever exploded” until that time. The event unleashed a colossal 200,000 megatons of energy, destroying buildings and infrastructure in Anchorage and far beyond; raising the land as much as 30 feet in some places; and sparking a major underwater landslide in Prince William Sound, which killed scores of people when the resulting waves slammed into Port Valdez.

When all was said and done, the 9.2-magnitude quake—which struck around 5:30 in the evening on Good Friday—and its many powerful aftershocks caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damage; killed more than 130 people (including more than a dozen tsunami-related deaths in Oregon and California) and; in ways literal and figurative, forever altered the Alaskan landscape in places such as Anchorage, Seward and Valdez.

Here, LIFE.com presents photos—many of them never published in LIFE—from the cataclysm’s aftermath.

Liz Ronk edited this gallery for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

Anchorage, Alaska, in the aftermath of the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake.

Bill Ray The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

The earthquake split the Turnagain section of Anchorage with a criss-cross of deep fissures in the ground, heaving the smashed homes up at crazy angles.

Bill Ray The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Aftermath of the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake, Alaska.

Stan Wayman The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Aftermath of the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake, Alaska.

Bill Ray The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Aftermath of the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake, Alaska.

Stan Wayman The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Alaskans prayed after the 1964 Good Friday Earthquake.

Bill Ray The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Ben Henry, 10, sat on bowling-game table in the Anchorage American Legion Hall as his sister Genevieve slept by the pins. Everything in their house was destroyed.

Bill Ray The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

People received medical treatment after the March 1964 Good Friday Earthquake, Alaska.

Bill Ray The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Alaska earthquake, 1964.

Bill Ray The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

After the March 1964 Good Friday earthquake, Alaska.

Bill Ray The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Relief supplies were unloaded after the March 1964 Good Friday Earthquake, Alaska.

Bill Ray The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

After the March 1964 Good Friday earthquake, Alaska.

Stan Wayman The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

After the March 1964 Good Friday earthquake, Alaska.

Bill Ray The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

After the March 1964 Good Friday earthquake, Alaska.

Stan Wayman The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

After the March 1964 Good Friday earthquake, Alaska.

Stan Wayman The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

After the March 1964 Good Friday earthquake, Alaska.

Bill Ray The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

After the March 1964 Good Friday earthquake, Alaska.

Bill Ray The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

After the March 1964 Good Friday earthquake, Alaska.

Stan Wayman The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

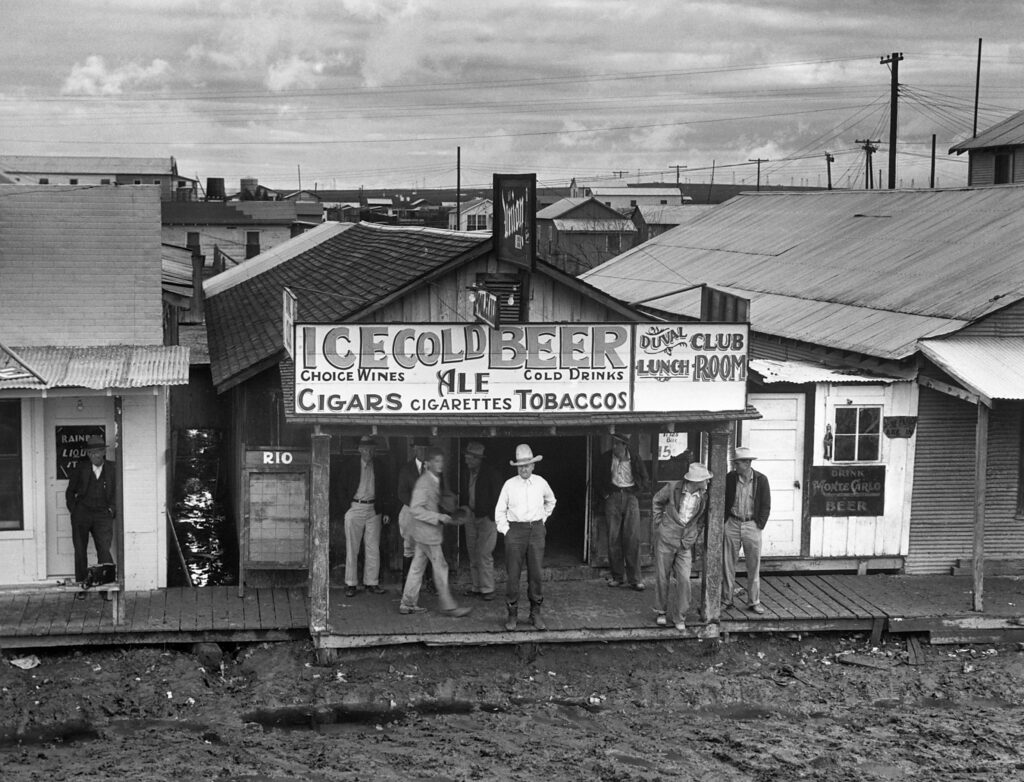

In downtown Anchorage, the buildings and the pavement dropped 20 feet, dividing Fourth Avenue into two levels and leaving a weird jumble of signs.

Stan Wayman The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Cover of LIFE Magazine April 10, 1964

LIFE Magazine

![Sagebush and sand surrounded Oklahoma farmer John Barnett's house and farm buildings. There was no topsoil left on the 160 acres. He grew rye and fodder in sandy loam. "Sagebush and sand surround [Oklahoma farmer John] Barnett's house and farm buildings. There is no topsoil left on the 160 acres. He grows rye and fodder in sandy loam."](https://static.life.com/wp-content/uploads/migrated/2014/10/dust-bowl-04-1024x811.jpg)