The following is from the LIFE’s new special issue on the music of Motown, available at newsstands and online.

Throughout 1988, the pressure on Berry Gordy Jr. was relentless. After almost three decades running Motown Records, Gordy was negotiating to sell the label, one of the country’s largest and most famous—yet floundering—Black-owned businesses. Gordy’s employees were unhappy about the deal. So were his peers. Democratic presidential candidate Jesse Jackson even cornered Gordy at a fundraiser, declaring that “selling Motown would be a blow to Black people all over the world.”

Gordy was unswayed. On June 29, 1988, the 58-year-old signed on the dotted line, transferring ownership of Motown to rival MCA Inc. and an investment firm for $61 million. “Do they know I’m losing millions?” Gordy wrote in his 1994 autobiography, To Be Loved: The Music, the Magic, the Memories of Motown. “How in the hell can anybody tell me I can’t sell something I created, nurtured and built from nothing?”

The record man had a point. From the day in January 1959 when he opened shop in downtown Detroit, Gordy had dedicated his life to Motown, ignoring the odds and naysayers to shape a business that would change contemporary culture. You know the names: Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, the Temptations, Diana Ross and the Supremes, Marvin Gaye, the Four Tops, Stevie Wonder, the Jackson 5. You know the songs: “Please Mr. Postman,” “Heat Wave,” “Where Did Our Love Go,” “My Girl,” and “What’s Going On.” It was music that not only dominated the charts for more than a decade, it gave shape to the national conversation. While civil rights protesters in the 1960s and ’70s voiced Black demands for full equality, it was Motown’s music that brought African American voices and faces into homes across the nation, introducing baby boomers and their parents to Black culture.

Motown’s success was progress itself. At the time when Gordy hung out his shingle, the nation, still largely segregated, offered few opportunities for Black artists hoping to break into entertainment or any other field. The Civil Rights Act prohibiting racial discrimination was years away. So was the Voting Rights Act, which ended racist southern laws preventing African Americans from casting their ballots. As a Black man and president of a record company, Gordy experienced not only prejudice and discrimination, but disbelief: “When I went to the white radio stations to get records played, they would laugh at me,” he recalled in a 2008 Vanity Fair interview.

Motown had good company in its quest to promote African American music. Chess, headquartered in Chicago, and New York’s Atlantic Records boasted a murderer’s row of rock & roll poets, blues rebels, and R&B immortals. Stax Records, in Memphis, was home to a grittier, Blacker sound, embodied by Otis Redding and Sam & Dave. But of the four rivals, Motown was the only fully Black-owned operation, and though critics accused the recording company of watering down Black music and sanitizing lyrics to bolster the bottom line, Gordy saw nothing to apologize for in his ambitions. “I wanted songs for the whites, Blacks, the Jews, Gentiles . . . I wanted everybody to enjoy my music,” Gordy told The Telegraph in 2016.

Up until the early 20th century, the options for Black recording artists were limited. There were some Black-owned imprints like Black Swan and Black Patti, which released so-called race records—music by and for African Americans—providing a platform for artists of color. Then, in the 1920s jazz started to stir the pot. Black and white kids were dancing to the big band anthems of African American composers like Duke Ellington, Earl Hines, and Count Basie. White clarinetist Benny Goodman began touring with an integrated group of musicians. Soon the “swing era” gave birth to “jump blues,” an early form of R&B that in turn teed up the ’50s rock & roll explosion.

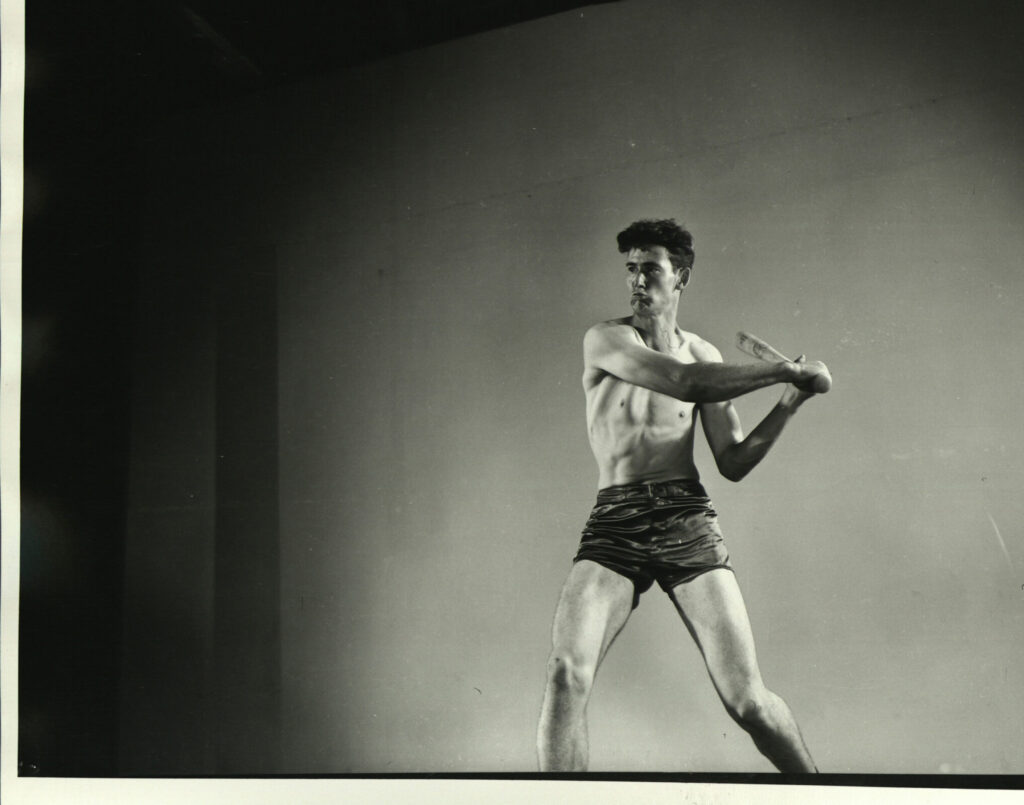

For Gordy, a budding songwriter who came from a music-loving family, the stage was set. After a few career detours—he had boxed professionally, briefly owned a record store, and worked on the Ford assembly line—the Detroit native serendipitously landed a gig writing for Jackie Wilson, an early soul star. But when he was shorted royalties and cheated of writing credits, Gordy grew frustrated. “Why work for the man?” he was asked by his protégé, a teenager named Smokey Robinson, who would go on to score Motown’s first million seller, “Shop Around” (1960), with the Miracles. “Why not you be the man?”

It was a good question, and Gordy answered it by securing a recording studio—he named it Hitsville U.S.A.—and understanding that to make those hits he would need to appeal to both Black and white record buyers. What’s more, to achieve that universal sound, he would have to exercise tight control over the product, which he did by applying lessons he learned on the Ford assembly line to music recording. Moreover, he would have to gain acceptance in the white-run music industry—a taller order. He fought for better conditions for his performers. He fought to book his acts in predominantly white clubs like the Copacabana in New York City and high-roller venues in Las Vegas.

“When the Supremes played the Copa—and everybody’s dream was to play the Copa—we all got caught up in the thing that you had to be different, that our music wasn’t good enough for places like that,” Gordy told Billboard in 1994. “We hadn’t realized how important our music was; none of us had ever been to the Copa.”

And then he began to score hits, then crossover hits, then No. 1 pop-chart hits, and suddenly Motown felt like it was everywhere. In the summer of 1964, Martha and the Vandellas’ “Dancing in the Street” became an anthem for both peaceful civil rights rallies and defiant race riots in American inner cities. After Black Panther leader Fred Hampton was gunned down by police in 1969, it was the Supremes’ soaring “Someday We’ll Be Together” that blasted from speakers at Hampton’s funeral. When Motown made the leap into the movie business, the company’s first project, Lady Sings the Blues, with Diana Ross as jazz vocalist Billie Holiday—received five Academy Award nominations, and the soundtrack hit No. 1 on the Billboard 200 album list.

Perhaps inevitably, as the 1970s and ’80s progressed and Motown’s classic acts matured, the label began to lose its luster. Sure, it added huge stars, including the Commodores, Rick James, and later a solo Lionel Richie, yet even more defected, and increasingly Motown’s music felt stuck in time. Twice in the 1990s the label changed hands; in the 2000s it slid further from view in a shuffle of corporate turnovers. But when Universal Music Group bought EMI’s recorded music division in 2011 and Motown became a subsidiary of Capitol Records, the label found a second life. After years of avoiding hip-hop and rap, Motown began to sign more current voices and was thrust back into the mix. It brought on Lil Yachty, Migos, and Lil Baby. Rolling Stone declared that the label “got its groove back.”

Today, Motown Records exists beyond its music label confines. It is Black history and Black excellence. It is commercial and beyond commerce, with classic songs appearing in commercials and films and Broadway shows, and a legacy that extends into today’s music, fashion, video games, and even slang. When Berry Gordy Jr. started his little record company in 1959, he saw the possibilities of universal music. He saw the future—that Motown would be America.

Enjoy this sampling of photos from LIFE’s new special issue on Motown.

(clockwise from top left) CA/Redferns/Getty; RB/Redferns/Getty; Ron Howard/Redferns/Getty; Echoes/Redferns/Getty

James Brown performed with his band in 1958.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

Martha and the Vandellas had record buyers dancin’ in the streets, circa 1960.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

Gladys Knight and the Pips, whose version of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine” was a breakout hit for Motown.

RB/Redferns/Getty

Marvin Gaye (center) and Martha and the Vandellas performed at the Apollo Theater, 1962.

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

The Four Tops rehearsed with choreographer Cholly Atkins (left) in the basement of the Apollo Theater, 1964.

Don Paulsen/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

Motown founder Berry Gordy played the piano as a group including Smokey Robinson (rear) and Stevie Wonder (second from right) sang together at Motown Studios, 1964.

Steve Kagan/The Chronicle Collection/Getty

From left: members of Martha Reeves and the Vandellas, The Temptations, Dusty Springfield, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Stevie Wonder and The Supremes performed with The Earl Van Dyke Sextet on The Sound of Motown special for Ready Steady Go! in North London, March 1965.

Popperfoto/Getty

The Supremes on the streets of Detroit in a performance recorded for television, 1965.

Donaldson Collection/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty

The Jacksons (clockwise left to right: Jackie, Marlon, Tito, Jermaine, and Michael) join parents Joe and Katherine in their backyard in Encino, California in 1970.

John Olson; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Berry Gordy, the founder of Motown Records, in 1970.

RB/Redferns/Getty

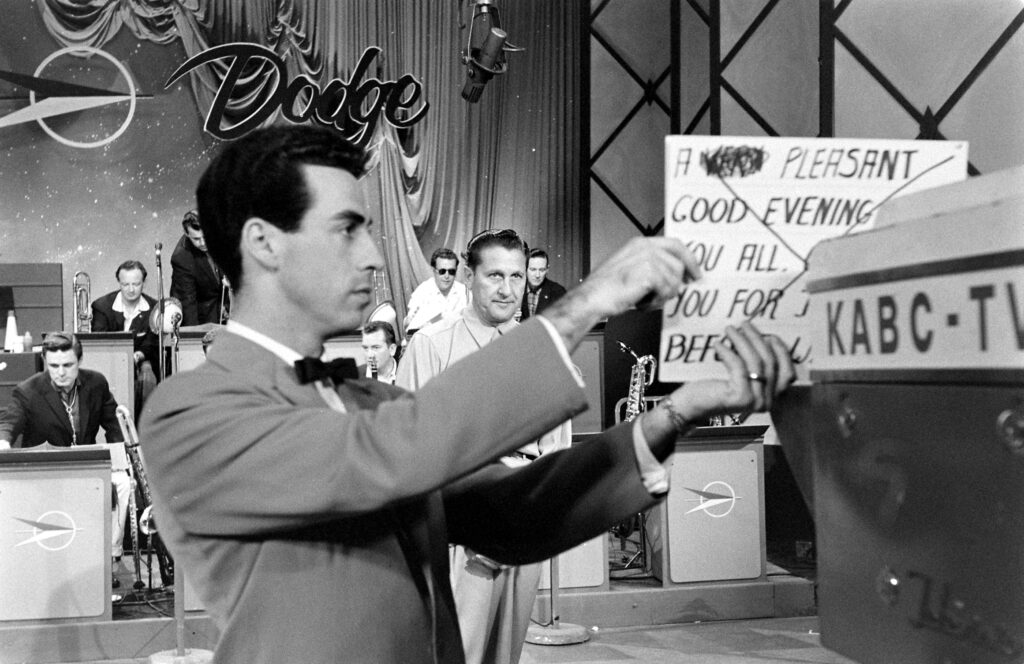

The Temptations performed on the ABC television show In Concert, 1973.

ABC/Getty

Smokey Robinson, Stevie Wonder, Andra Day, and the cast of the Broadway show Ain’t Too Proud: The Life and Times of the Temptations performed when Motown founder Berry Gordy was honored at the Kennedy Center, 2021.

Scott Suchman/CBS/Getty