National Nurses Week, which begins May 6, recognizes the millions of nurses who make up the backbone of the American healthcare system. And the annual shout-out is more than warranted: A 2014 survey of more than 3,000 nurses found respondents to be stressed out, underslept and — at least in their own estimation — underpaid.

When LIFE featured the profession on its cover in 1938, the career was in a moment of transition. “Once almost any girl could be a nurse,” LIFE explained, “But now, with many state laws to protect the patient, nursing has become an exacting profession.” A candidate needed not only a background in science, but also a combination of “patience, devotion, tact and the reassuring charm that comes only from a fine balance of physical health and adjusted personality.”

Nurses also needed, as they still do, stamina. A typical day in the life of a Roosevelt Hospital School of Nursing student who had been capped — meaning she had successfully completed the probationary period — was described as follows:

Her day begins early. She rises at 6, breakfasts at 6:30, reports to duty at 6:55, has lunch sometime between 12 and 1:30. The rest of the day is consumed with ward duty, two hours of classes, three hours of rest or study. At 7 p.m. she is free to go out on parties, read in the library, dance in the reception room with her fellow nurses or make herself a late supper in the nurses” kitchen.

The photo essay, shot by Alfred Eisenstaedt, was an earnest nod to a group of people responsible not only for the well-being of individual patients, but also the public health of a city and a nation. Their duty, after all, was “to secure the health of future generations.”

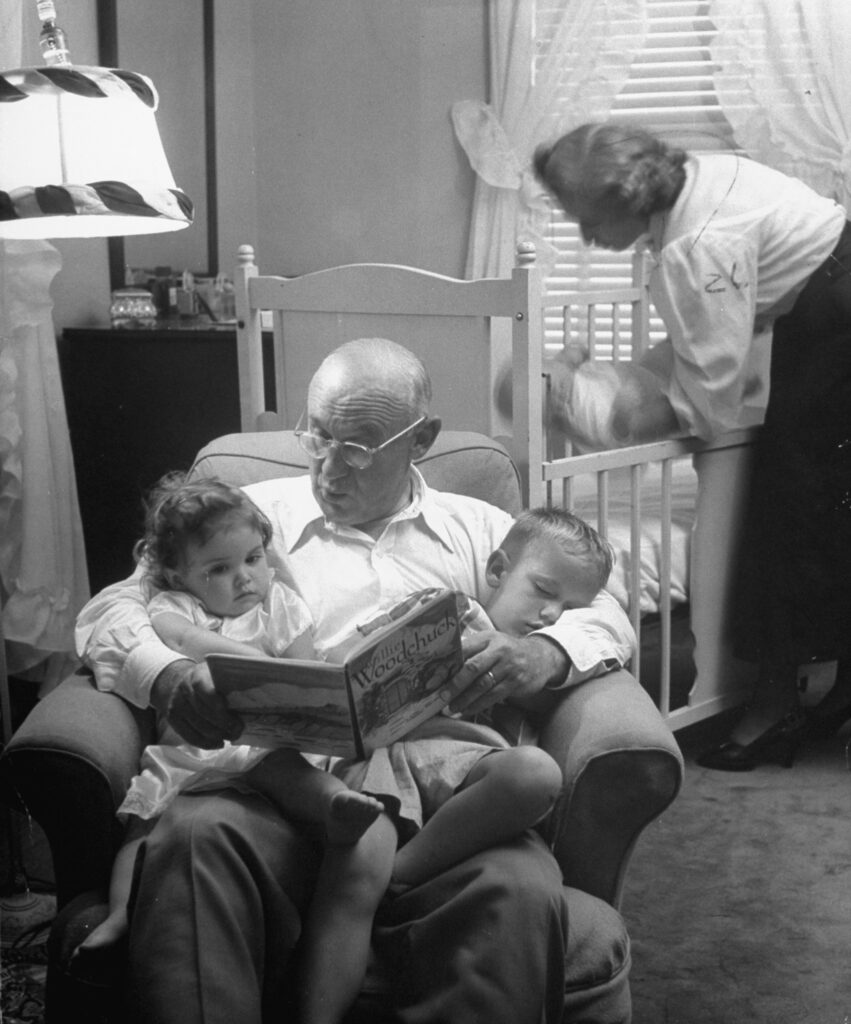

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Student nurses 1938

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock