When Oscar nominations are announced every year, the conversation turns quickly from who got nominated to who got snubbed. And people tend to react with more indignation over who’s missing than in celebration of who’s been recognized.

But the snub has been around since long before the age of Internet outrage, when gossip was relegated to soda fountains and opinions took days to make it from type-written notes to a Letters to the Editor page. And although we tend to associate Hollywood’s biggest stars with that bald, naked mini-man of gold, many of history’s most remembered actors and actresses never got their hands on a statuette.

On the actresses’ side, Marlene Dietrich, Ava Gardner and Dorothy Dandridge had to settle for nominations alone. Perhaps Natalie Wood and Jayne Mansfield would have been recognized eventually, had their lives not been cut so tragically short. Some actresses gave up a great deal for the roles that would leave them empty-handed. Janet Leigh, who was nominated for Psycho but didn’t win, spent the rest of her life afraid of the shower.

Among their male counterparts, things weren’t all bad. Richard Burton, nominated seven times for films including Becket (1964) and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966), was one of the highest-paid actors in the world at his peak. Peter Sellers, born in England, could take comfort in his two wins at the BAFTAs, Oscar’s cousin across the pond. And Steve McQueen could wipe his tears of dejection on that clean white t-shirt, though many, to be sure, preferred him without one at all.

Many repeated oversights were corrected, if not fully, with honorary Academy Awards doled out to stars in their golden years, although none of the actors and actresses pictured above even received one of those. For them, alas, money, fame, and a place in the annals of history would just have to suffice.

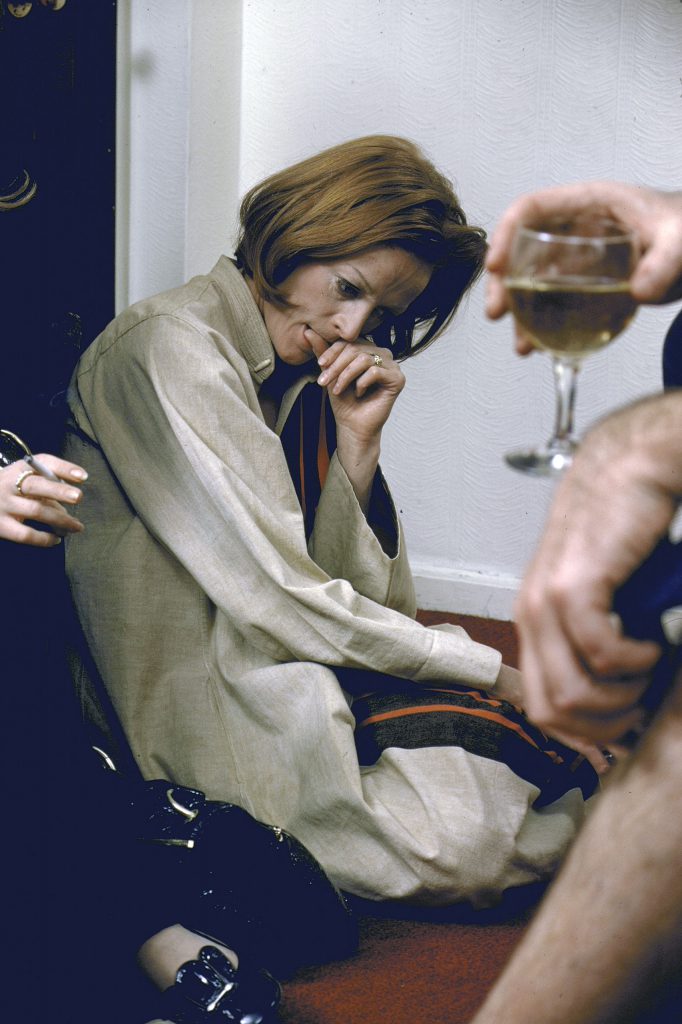

Natalie Wood, who received three nominations. Pictured at the Cannes FIlm Festival, 1962.

Paul Schutzer The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Steve McQueen, who was nominated once. Pictured here during motorcycle racing across the Mojave Desert, 1963.

John Dominis The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Rita Hayworth, 1945.

Bob Landry (The LIFE Picture Collection)

Jayne Mansfield, who was never nominated, though she once played violin in an orchestra performance at the Oscars. Pictured here posing with shapely hot water bottle likenesses floating around her in her pool, 1957.

Allan Grant The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Richard Burton, who was nominated seven times. Pictured relaxing with a book in Cantina while on location filming The Night of the Iguana, 1963.

Gjon Mili The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Erroll Flynn, who was never nominated. Pictured aboard his yacht Sirocco, 1941.

Peter Stackpole The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Lena Horne, shown here in Paris in 1947, was never nominated for an Oscar, though she was honored with a tribute at the 2011 Academy Awards.

Yale Joel The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Kim Novak, who was never nominated, though she presented at the 2014 awards. Pictured in the movie Jeanne Eagels, 1957.

J. R. Eyerman The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Tony Curtis, who was nominated once. Pictured with his Rolls Royce, 1961.

Ralph Crane The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Montgomery Clift, who was nominated four times. Pictired in Red River, 1948.

J. R. Eyerman The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Lana Turner, who was nominated once. Pictured here with John Garfield on Laguna Beach in a scene from The Postman Always Rings Twice, 1945.

Walter Sanders The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Dorothy Dandridge, who was nominated once, becoming the first African-American to be nominated for a leading role (1955). Pictured posing in costume for Tarzan’s Peril, 1951.

Ed Clark The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Douglas Fairbanks Jr., who was never nominated. Pictured in Sinbad, 1946.

Peter Stackpole The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

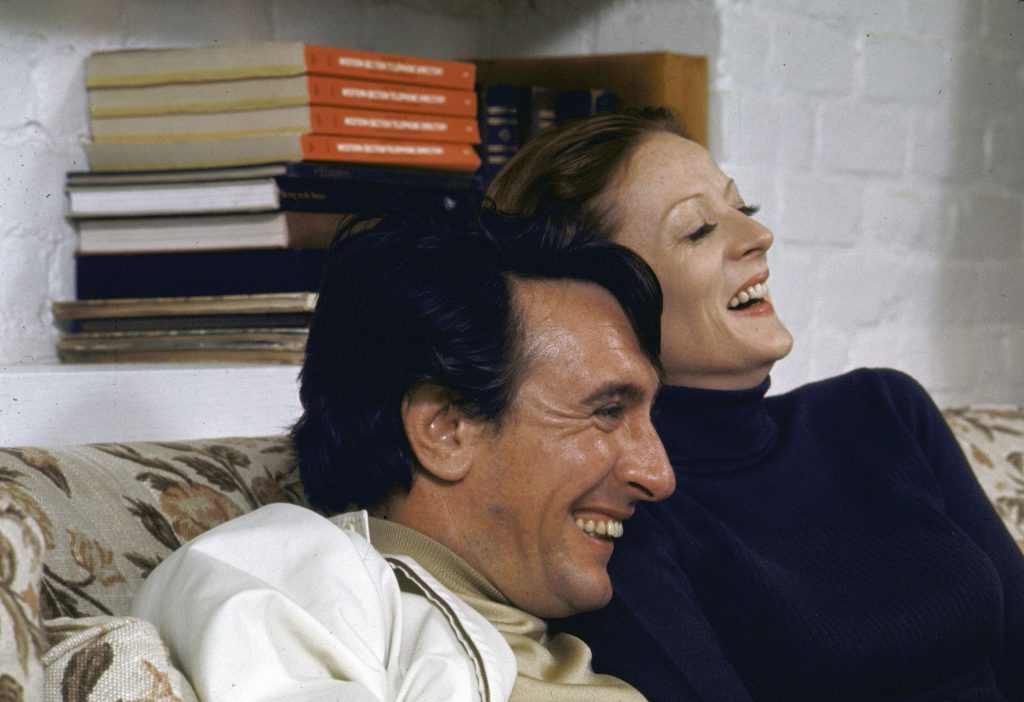

Peter Sellers, played the piano at home with his wife, Britt Ekland, in Beverly Hills, 1964.

Allan Grant The LIFE Images Collection/Shutterstock

Marlene Dietrich, who was nominated once. Pictured in evening dress and hat during Pierre Ball, 1928.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Ava Gardner, who was nominated once. Pictured in One Touch of Venus, 1948.

J. R. Eyerman The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Janet Leigh, who was nominated once. Pictured posing in costume for Jet Pilot, 1950.

Ed Clark The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Robert Walker, who was never nominated. Pictured riding a tricycle with his two sons, 1943.

John Florea The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Van Johnson, who was never nominated. Pictured duck hunting in a scene from the movie Early to Bed, 1945.

Martha Holmes The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock