Hearing the term “D-Day” might bring to mind images of violence. In photos, movies snd old news reels, and usually all in grim black-and-white, we have seen what happened on the beaches of Normandy (codenamed Omaha, Utah, Juno, Gold and Sword) as the Allies unleashed their historic assault against German defenses on June 6, 1944.

But in color photos taken before and after the invasion, LIFE magazine’s Frank Scherschel captured countless other, lesser-known scenes from the run-up to the D-Day and the heady weeks after: American troops training in small English towns; the French countryside, startingly lush after the spectral landscape of the beachheads; the reception GIs enjoyed en route to the capital; the jubilant liberation of Paris itself.

Scherschel’s pictures most of which were never published in LIFE are resented here in masterfully restored color and feel at-once familiar and somehow vividly new.

Scherschel, who died in 1981, was an award-winning photographer for LIFE well into the 1950s. (His younger brother Joe was a LIFE photographer, as well.) In addition to the Normandy invasion, Frank photographed the war in the Pacific, the 1947 wedding of Princess Elizabeth, the 1956 Democratic National Convention, collective farming in Czechoslovakia, Sir Winston Churchill (many times), art collector Peggy Guggenheim, road racing at Le Mans, baseball, football, boxing, a beard-growing contest in Michigan and countless other people and events, both epic and forgotten.

Information on the specific locations or people who appear in these photographs is not always available; Scherschel and his colleagues did not have the means to provide that data for each of the countless photographs they made throughout the war. When the locale or person depicted in an image in this gallery is known, it is noted in the caption.

Liz Ronk edited this gallery for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

American troops in England before D-Day, May 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

American combat engineers ate a meal atop boxes of ammunition stockpiled for the impending D-Day invasion, May 1944.

Frank Scherschel;Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Troops and civilians passed the time on Henley Bridge, Henley-on-Thames, in the spring of 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

An American corporal stacked cans of gasoline in preparation for the upcoming invasion of France, Stratford-upon-Avon, England, May 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

A small town in England in the spring of 1944, shortly before D-Day.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

An American Army chaplain knelt next to a wounded soldier, to administer the Eucharist and Last Rites, France, 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

An abandoned German machine gun, France, June 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Magazines scattered among the rubble of the heavily bombed town of Saint-L™, Normandy, France, summer 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

An American tank crew took a breather on the way through the town of Avranches, Normandy, summer 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“We thought it was going to be murder but it wasn’t. To show you how easy it was, I ate my bar of chocolate. In every other operational trip, I sweated so much the chocolate they gave us melted in my breast pocket.” – Frank Scherschel describing his experiences photographing the Normandy invasion from the air, before he joined Allied troops heading inland. Above: GIs searched ruined homes in western France after D-Day.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

View of the ruins of the Palais de Justice in the town of St. Lo, France, summer 1944. The red metal frame in the foreground is what’s left of an obliterated fire engine.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“All the civilized world loves France and Paris. Americans share this love with a special intimacy born in the kinship of our revolutions, our ideas and our alliances in two great wars.” – LIFE on the relationship between the U.S. and its longtime European ally

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Along the coast of France, June 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

From D-Day until Christmas 1944, German prisoners of war were shipped off to American detention facilities at a rate of 30,000 per month. Above: Captured German troops, June 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Maintenance work on an American P-47 Thunderbolt in a makeshift airfield in the French countryside, summer 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

A French couple shared cognac with an American tank crew, northern France, summer 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

A P-38 fighter plane sat in the background as the pilot arrived in a captured German vehicle, France, 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Church services in dappled sunlight, France, 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

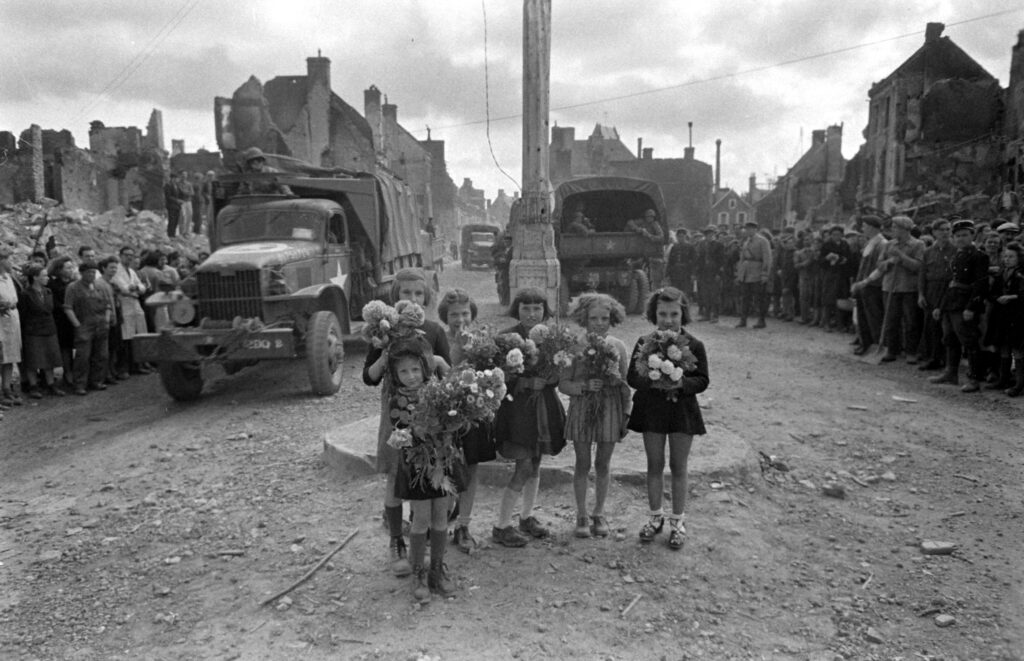

DAmerican Army trucks (note cyclist hitching a ride) paraded down the Champs-Elysees the day after the liberation of Paris by French and Allied troops, August 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Frenchmen transported painted British and American flags for use in a parade, summer 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Tanks under the Arc de Triomphe in Paris during liberation celebrations, August 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

“Paris is like a magic sword in a fairy tale – a shining power in those hands to which it rightly belongs, in other hands tinsel and lead. Whenever the City of Light changes hands, Western Civilization shifts its political balance. So it has been for seven centuries; so it was in 1940; so it was last week.” – LIFE after the French capital was liberated in August 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Free French General and military governor of the French capital Pierre Koenig, left, during ceremonies held the day after the liberation of Paris, August 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Celebrations in Paris after the liberation of the city, August 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

American troops stood beside a World War 1 monument bedecked with French flags after the town (exact location unknown) was liberated from German occupying forces, summer 1944.

Frank Scherschel; Life Pictures/Shutterstock

![As taps sounded, [French] President de Gaulle and [Ethiopian] Emperor Haile Selassie saluted the grave. As taps sounded, [French] President de Gaulle and [Ethiopian] Emperor Haile Selassie saluted the grave](https://static.life.com/wp-content/uploads/migrated/2014/11/141118-jfk-arlington-cemetery-12-1024x663.jpg)